Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

Victorian cage-bird fanciers of Brick Lane

JAMES GREENWOOD’S 1874 book The Wilds of London reports on the poorer areas of London and the ways of life of their inhabitants. At times a note of condescension creeps into his writing, but Greenwood is broadly sympathetic to the plight of the poor and he writes in a brisk and vivid style.

Greenwood came from a large London working-class family and he started out as an apprentice compositor, a ‘labour aristocracy’ trade demanding dexterity of hand and mind. His brother Frederick became a journalist and, as editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, began commissioning James to visit the slums of London and write articles about what he encountered there.

The third chapter of the The Wilds of London is titled Sunday evening with the ‘Fancy’ and in it Greenwood provides a glimpse of an East End fraternity based around an interest in cage birds and terriers. The sounds of birdsong form a central theme. His description begins with a walk along Hare Street off Brick Lane.

Booth’s Poverty Map of 1898 shows the area. You can make out Hare Street just behind the parish name of St Matthias. Brick Lane runs vertically to the east, passing by the vast Truman brewery complex. The colour-coding of the dwellings around there shows that many of the inhabitants were very poor. Hare Street no longer exists in its own right, having been engulfed by the westward march of Cheshire Street.

Greenwood then visits a pub on Brick Lane which he doesn’t name. It turns out to be a meeting-place for the bird-fanciers of the East End:

There were a good many performers before the bar, and before every man had re-plighted his troth and put himself in condition to discuss ordinary topics, my measure of Brick Lane beer was considerably reduced. But alas! even when they began to talk I was almost as much in the dark as ever. The conversation was strictly birdy. One person was bragging of him ‘slamming’ goldfinch, and there was a dispute as to how many ‘slams’ it could execute within a given time. Another individual button-holed a friend, and told him all about his ‘greypates,’ while a third was learned on the subject of linnets, and recited that able bird’s sixty-four distinct notes, but of which the only sentence I could make out was ‘Tollic, tollic, tollic, chew-chew-tew-wit-joey,’ and as the man had a very gruff voice and gave the recitation with a strong nasal twang, I am afraid that my ideas of the linnet’s song were not exalted by the lesson.

There was presently some talk about chaffinches and ‘chaffinch matches,’ and then I began to glean a little real information. I learned that in the very house we were then in the ‘muffin man’ had sung his bird against another songster the property of a gentleman whom the company spoke of as ‘More-Antique,’ on the previous Thursday, for £3 a side, and that More-Antique had lost by three chalks. The terms of the said match appeared to be that each man hung up his bird against the wall, in the position he best fancied, and that the finch that uttered the greatest number of perfect notes within the space of fifteen minutes – an impartial person sitting at a table, and chalking down the notes as they were delivered – should be the winner. A ‘perfect note,’ as described by the gentleman who was so great in linnets, was ‘toll-loll-loll chuck weedo,’ and if in its utterance the bird abated a single syllable of the note it didn’t count in the scoring.

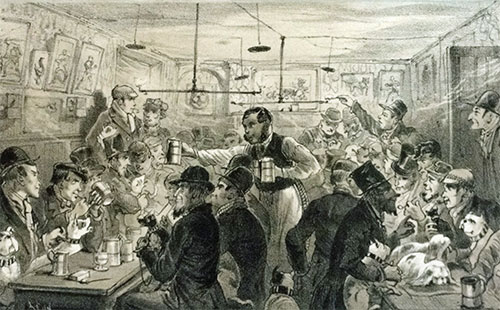

Later, Greenwood visits another pub called the Tinker’s Arms, where he encounters dog-fanciers. Here’s the illustration from The Wilds of London:

The tradition of keeping songbirds in cages is often ascribed to Flemish weavers, who settled in significant numbers in Spitalfields and elsewhere in England, notably Norwich, where they introduced canaries as pets. It seems likely that the birds were kept to make a pleasant sound to ameliorate the repetitive work of weaving, filling the same role as the tradesman’s radio.

But what Greenwood describes is different: an informal men’s club meeting outside the workplace for socialising and rules-bound competition. Such songbird contests don’t seem to exist in England any more, but they still carry on under the name of vinkensport (‘finch sport’) in the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders in Belgium. This 2007 New York Times article delves into the world of vinkensport, where not everyone sticks to the rules:

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology