Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

Street noise and the taming of Victorian London

WITH THE HELP of the Times Digital Archive it’s possible to gain a rough idea of how upper and middle-class reactions to street noise changed during the 19th century.

At the beginning of the century objections to street noise from Times editorials and letter-writers tend to be framed in moral terms. In the latter half of the century, the idea that noise has a special impact on intellectual labour becomes more commonly expressed. This may reflect a rise in a Galtonian form of class consciousness. That is, the belief that social stratification reflects differences in intellectual capacity and that civilised life depends on the most intelligent classes having full freedom of action.

The letters also reveal a great deal about the street sounds of everyday life in London, even when allowing for a degree of exaggeration on the part of their writers.

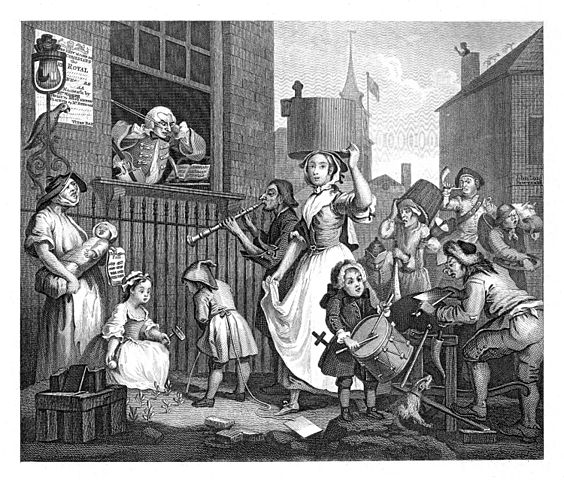

Attempts to control noise in London go back to local laws in the Middle Ages when clamorous trades involving metal-working were subject to curfews. Street vendors’ cries were often celebrated in poems as emblematic of the city’s commercial spirit, but Hogarth’s 1741 engraving The Enraged Musician shows them interfering with a specific line of work:

One of the earliest complaints in the 19th century is about noise in theatres because too many lower-class people who don’t know how to behave are being let in. This letter is from the Times dated 6 October 1808:

The writer proposes an easy solution: stop selling cheap tickets, which in any event threaten to bankrupt the theatre. Blame is therefore split between the lower orders, whose behaviour is to be expected, and the theatre owners, who should know better. The theme of noisy theatres resurfaces in 1828 with a brief spate of correspondence on the subject and after then it largely disappears from the letters pages.

The blameworthiness of commercial interests is stated more clearly in a letter from ‘A Middlesex Magistate’ in November 1815 about noisy taverns:

As the 19th century progressed and Britain escaped from the Malthusian trap with productivity surpassing population growth, London’s inhabitants multiplied six-fold. The sustained response by elites to what Thomas Carlyle called the threat of ‘swarmery’ and the disorder flowing from it was a full-on program of behaviour modification designed to domesticate the lower classes. The conclusion of Jerry White’s book London in the Nineteenth Century is that these efforts were largely successful on their own terms.

However, social engineering on that scale wasn’t conceivable to the Times editorial writer of 1817. In this extract, he describes two separate realms: the court of law, where noise can and should be suppressed, and the street outside, where it cannot and should not:

The trials of the riots were continued yesterday at the Old Bailey, and produced several convictions for larcenies. The process of the elder Watson took place last, under the Cutting and Maiming Act, who was very properly acquitted, and recommended to be so acquitted by the Counsel for the Crown, on account of the insufficiency of the evidence to prove the malicious disposition of the prisoner. Upon Watson’s acquittal, we learn that a loud expression of satisfaction burst forth from several persons in Court, which was severely and justly, as is usual in such cases, reprehended by Mr. Justice PARK. Surely the decorum and decencies of our Courts of Law, which are our strong refuge of liberty, should be observed, or else law and order had better be abolished by act of Parliament.

When the noise in Court had subsided, a fresh burst of huzzaing and clapping broke forther in the streets, as soon as the news of Watson’s acquittal was known; and here one might have more doubt about the learned Judge’s competence to interfere in a summary way: undoubtedly he would have a right to abate or remove a nuisance, or to suppress any obstruction whatever to the proceedings of the Court; but yet, to send a man to prison, without previous notice, for making a noise in the King’s highway, might appear to be a somewhat compendious exercise of law.

Greater efforts to control street noises were made later that year when church services were threatened by the blowing of coachmen’s horns:

But little was done about such nuisances when the rituals of worship were not directly affected. In 1819 ‘Castigator’ from Gloucester Place complained about ‘the perpetual clangor of the horns used by the drivers of the Paddington stages, in their passage through the New-road, to announce their departure for the city’. Even worse, the coachmen were ‘not content with blowing as they pass, they are pleased to wait for a full quarter of an hour at the ends of the contiguous streets in perpetual succession, there to play most stunning solos’.

The authorities could only do so much, and some noise complaints betray a sense of impotence in the extravagant remedies put forward. In 1825 a resident of Goswell Street was driven to a high level of fury by the noise and fecundity of stray dogs:

The writer goes on to suggest that parish relief be withdrawn from dog owners and that all strays be rounded up, killed and their hides turned into dog-leather, which apparently is the most waterproof of all.

The themes of public disorder and immorality were raised later in 1825 by ‘An Inhabitant of Islington’:

The most explicit connection between noisy disturbances and sin was drawn in 1828 by ‘An Old Under Sheriff’ outraged at the increasing scale of the entertainments laid on at the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens:

In my letter inserted on the 9th of October last, I considered the moral nuisance of Vauxhall, under its present management, and observed that the noise of the exhibition of the battle of Waterloo could only be compared to the cannonading pf a town, and infinitely surpassed any inconvenience which has been felt from the fireworks; that this noise, protracted as it was to a very long period, conveyed through an extensive and thickly-populated district the exact effect of artillery and platton firing; and that while the industrious were this prevented from sleeping, the sick were more seriously distressed, and the dying forbidden the consolation of departing in peace. [. . .]

It is now understood that the battle of Waterloo is to be succeeded by the battle of Navarino, and of course that nocturnal disturbance of the ensuing season will in no way yield to that of the last, while the same disgusting orgies of lust and drunkenness which have long characterized this place within, and rendered it a terror to the neighbourhood without, will of course go on, to the utter scandal of our common Christianity.

This time the complaint was met with several unsympathetic rebuttals. One, pointedly signed ‘A Young Under Sheriff’, described it as ‘pious twaddle’. Not everyone disliked occasional loud noise.

Three years earlier, a letter even tried to recruit street noise into the service of morality. ‘F.C.’ condemned the habits of the ‘gaming gentry’ in the gambling dens of St James’s, urging that churchwardens be given the same powers to drive out their clients through public shaming as they were able to do with the ‘inmates of bad houses’. But there was a fall-back plan if the first one didn’t work.

I would recommend the churchwardens to get all the hurdy-gurdy men in the metropolis to go to each gaming-house, and cause them to play, alias, make as much noise as they could, as a means of annoyance, to disturb the gentry at their amusement.

I have heard of one Savoyard, who made a practice of going daily to King-street, St. James’s, where he stationed himself, and certainly did not spare either his lungs or his guitar. This had such an effect on the players, who had the distraction of play to contend with, that they rose in a body, and went from that house to another. The bankers were obliged to give the cunning Savoyard a quietes to induce him to desist. This quietus he daily receives, and he exacts from others large sums in the same way.

This indulgent attitude towards immigrant street musicians did not become the norm. A letter from June 1828 was among the first in the Times to identify street music as a growing problem.

Immigration to London from continental Europe grew during the 19th century and the numbers of German street bands and Italian organ-grinders became a bellwether provoking well-publicised annoyance. A campaign against street music counted among its supporters Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle, the mathematician Charles Babbage, and sections of the press. This eventually led to the passage of the Street Music (Metropolis) Act in 1864.

However, a flurry of letters in the summer of 1869 suggests that the thoroughness with which the law was applied depended on differences in tolerance on the part of individual policemen. This example filters its writer’s sense of exasperation through a languid humour:

The tone adopted by ‘M.D.’ of Harley Street, writing a few days earlier, shows a greater strain on the nerves. Not only are the police failing to do their job properly, but the racket of night-time London has a particular impact on the intellectual class of professional men and decision-makers. M.D. sees that his interests and those of his class are identical.

The police should be made to keep our streets quiet during certain hours of the night. No attempt at this is made at present. The night policemen walk tacitly up and down, while every house in the street is being roused by the most abominable noises, without their making the slightest attempt at checking them. It might not unfairly be asked that people should have a chance of sleeping from 12 o’clock till 8; but in the name of all that is sane, let them have the possibility of sleeping from 2 o’clock till 8.

There is no such chance now. No one interferes to stop any amount of noise in the night and early morning. A party of cats may hold an uproarious concert in the middle of the road without even a ‘‘hiss’’ from the policeman to disperse them. Two ‘‘cabbies’’ may career down the opposite gutters, and hold a conversation across the road at the top of their voices. A train of scavengers’ carts may be driven down the streets, rumbling like thunder, while the driver in the last cart holloas his jokes to the man in the front. In some districts it is thought necessary to create the most infernal noise about 5 o’clock in the morning by setting a host of garrulous old men to scrape and stone the roads at that pleasant hour. On Sunday mornings the paper boys are allowed to bawl with all their might. At any hour of the night a fool in love with concertina may disturb a whole neighbourhood with the noise he pleases to think music; and no interruption is given to any number of drunken rollickers who choose to sing and holloa up and down our streets and squares.

I have said nothing of the early organ-grinders, collectors of hares’ and rabbits’ skins, sellers of watercresses, the inevitable dustman, the rows attendant upon balls and receptions, or a hundred other sleep preventers, too painfully familiar to those who turn in their beds between 12 and 3 o’clock in the morning, their brains fagged and excited by work – Parliamentary, scientific, judicial, professional, it matters not which, or even by those unavoidable and wearying pursuits of social life which we call ‘society’.

The identification of high social standing with intellectual excellence had been set forth earlier that year in Francis Galton’s influential book Hereditary Genius:

Another letter-writer from September 1869, signing himself ‘A Hater of Noise’, doesn’t identify himself with the governing class, and indeed may have been a clerk or accountant. But he perceives a gulf between himself and the itinerant traders who disturb him, suggesting that much of their noise has no purpose, which may well have been the case:

I live in what is called a quiet street. My occupation demands fixed and sometimes strained attention, and moderate quiet is almost a necessity. Yet the best hours of the day are invaded by the hideous bawling of hawkers of vegetables, fish, &c. From towards noon to the early afternoon, during which time, it is presumed, these animated nuisances are renovating themselces for fresh energies, the noises in a measure cease; then come the shrill voices, old and young, ragged and torn, with their walnuts, watercresses, &c., until such time as the clock gives warning to discontinue work for the day. I believe I am but stating the case of thousands who are similar sufferers to myself, to say nothing of sick persons, to whom these noises must be little less than agony.

As far as my own observation extends, this hawking is not demanded by the public. I have watched costermongers and other hawkers pass the length of whole streets without finding a single customer. That the trade is miserably bad is proved by their repassing the same street, a fact of which I am only too vividly cognizant.

I would, therefore, risking the displeasure of the kind-hearted who might want to know why people should be prevented getting an honest living, ask, through your columns, that something be done to protect those who get their living by, truly, the sweat of their brows from others who do so by the noise of their voices.

Towards the end of the century the forces of order had established a permanent and mostly constant control over street life in the central areas inhabited by London’s wealthiest citizens. Intrusive noises were increasingly described by Times letter-writers as arising from failures of organisation and technique rather than morality. One letter, dating from 1890, even argued for the return of the horns which had been vexatious several decades before:

Other debates revolved around the desirability of asphalt paving versus newer road surfaces such as hardwood blocks, or the need for Post Office coaches to have india-rubber tyres. In 1895, a letter addressed from a member of the Athenaeum Club framed the issue in almost domestic terms:

With the triumph of order from above, it was now expected that the model of conduct within the homes of the wealthy could at last be laid out across the city’s streets.

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology