Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

Five fundamental stances in recording

DIFFERENCES IN THE practice of sound recording are usually thought of in terms of technique and subject matter. Studio recording is contrasted with field recording. Interviews occupy a realm separate from wildlife sounds. A recordist expands their repertoire by getting a contact mic to make audible the vibrations racing through solid objects.

Ways to change your recording approach include things like investing in new kit, travelling more widely or thinking of different subjects to record. Such decisions don’t happen in a vacuum. They’re influenced by established traditions in recording, the demands of work, and one’s own personality and preferred ways of dealing with people and the environment.

A while ago I tried a rough summary of these influences and their role as parameters, like switch settings, from which more precise decisions cascade:

The fundamental issue in recording is the relationship between the recordist and their subject.

The relationship which actually emerges in real life might not be the one which you set out to achieve. Things don’t always go according to plan. But at the level of intentions at least there exist what I’ll call stances, which are relatively stable and enduring ways of working and thinking about recording.

Here I’ll describe five possible kinds of stance: observational, self-reflexive, collaborative, transformative, and data gathering.

OBSERVATIONAL

The observational stance is involved in most of what’s described as field recording. Its goal is to record sounds which would occur anyway if they weren’t being recorded. It then processes and presents them so that there is an explicit correspondence between the finished recording and the original sound source.

The logic of the observational stance demands efforts to ensure that the flow of information is one-way, from the subject to the recordist. It also tends to push recordists towards obtaining the highest fidelity or sound quality they can manage.

Almost unique to the stance is an interest in auditory arrays where there is no single focus of interest and which are comprised of many independent sound sources, as with the recording of urban and rural soundscapes.

SELF-REFLEXIVE

The self-reflexive stance is taken when the recordist is the subject. Obvious examples include audio diaries, many podcasts, aides memoire made on voice recorders and mobile phones, and solo musicianship.

The flow of information is that of a feedback system, as the recordist monitors their own sounds and speech. There is a single focus of interest in the auditory array.

COLLABORATIVE

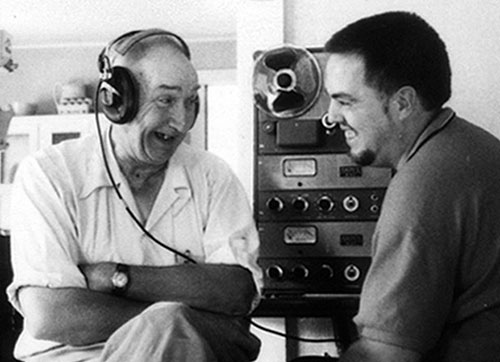

To a first approximation, most recorded and broadcast sound is made in the collaborative stance. The subject is aware of the recordist’s presence and the act of recording involves some form of consent, either tacit or explicit. Examples include studio recording, oral history interviews, and news gathering.

Information flows between the recordist and the subject in a two-way interaction. Typically there’s a single focus of interest whether the subject is a lone individual or a collective entity like a band.

TRANSFORMATIVE

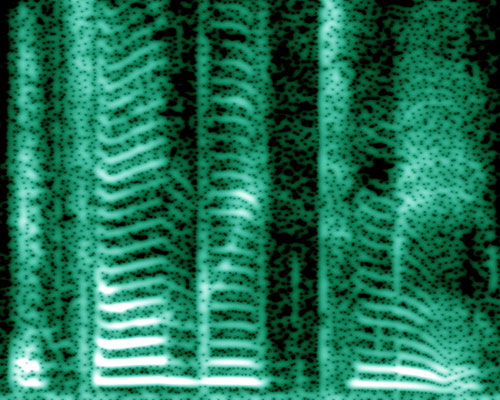

Recordings can be made without the intention to represent their original context, meaning or nature. They may be changed beyond recognition by processing or else be given new meanings, not easily predictable from their origins, by contributing to larger creative works. The transformative stance is commonly adopted by foley artists, sound artists, and experimental musicians.

Information flow most closely resembles a feedback system when the creative goal is precisely defined in advance.

DATA GATHERING

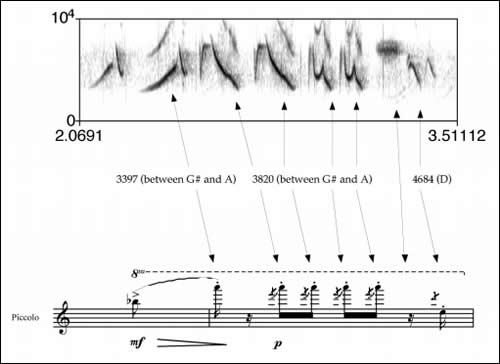

The data gathering stance is taken in scientific and engineering research where the reproduction of sounds is not the primary goal, but rather the identification, sorting, or quantification of elements within a sound signal. Examples of such work include speech analysis, machine learning, and research into animal communication and biodiversity.

The flow of information is made explicit in experimental designs, with sounds often representing a dependent variable and attempts made to control for confounding factors.

This simple scheme isn’t exhaustive: the post isn’t titled the five fundamental stances in recording. They surely don’t comprise mutually-exclusive domains. But I think it might be a useful way of thinking about recording, because it requires taking a step back from the immediate details of our habits to consider how we intend acting in the world.

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology