Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

Arthur Machen: the sounds from beyond the veil

ADVENTURES MADE EARLY in life can go on to define intellectual careers and reputations. Darwin was 22 when he set off on The Beagle. T. E. Lawrence built a personal mythos from his experiences as a young officer during the Arab Revolt of 1916–18. The anthropologist Margaret Mead was 27 when her book Coming of Age in Samoa was published, while Napoleon Chagnon spent his twenties studying the Yanonamo people, sometimes introducing himself to a new village by leaping into its central clearing with his face daubed in war paint, waving a shotgun.

The Welsh-born mystic and writer Arthur Machen moved to London in 1881 when he was in his late teens, a good age for the kind of long exploratory walks which can bring on a trance-like state of fatigue. He lodged briefly in south London before moving to Turnham Green, then Notting Hill Gate. With De Quincey’s opium-powered London wanderings sometimes in mind, Machen began first to explore the north and west of the city. His autobiographical works, such as Far Off Things (1922), suggest he gathered enough thoughts on London and its hinterlands during these expeditions to inform the rest of his literary career.

Machen’s descriptions of sounds often occur in the absence of seeing what’s making them. In The Terror (1917), a part of the Welsh countryside is haunted by an eerie, distant moaning, which is later revealed as people crying for help up the chimney flue of a barricaded cottage. A Fragment of Life (1899) features a nature spirit less benign than Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill, which whistles unseen at a couple walking in the fields near Totteridge. The confrontation is a foretaste of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now:

Part of H.P. Lovecraft’s acknowledged debt to Machen also lies in hearing without seeing. Well before Lovecraft’s half-human ululations emanated from somewhere below ground, Machen’s The Three Impostors (1895) has Francis Leicester ingest a restorative white powder from a chemist, only to undergo a horrible physical degeneration. The process takes time, however, as his sister finds out:

“Francis, Francis,” I cried, “for heaven’s sake answer me. What is the horrible thing in your room? Cast it out, Francis, cast it from you!”

I heard a noise as of feet shuffling slowly and awkwardly, and a choking, gurgling sound, as if some one was struggling to find utterance, and then the noise of a voice, broken and stifled, and words that I could scarcely understand.

Sound in Machen’s writings can create a tunnel between the present and a different time or place. Another vignette from The Three Impostors underlines his influence on Lovecraft. A feeble-minded youth named Jervase Cradock is taken on as a gardener and suffers a fit while at his work:

In the semi-autobiographical The Hill of Dreams (1907), the young writer Lucian begins to disintegrate mentally amid his isolation in a west London suburb and his failure to achieve the numinous prose he strives for. The memory of a storm from his childhood in Wales comes back to him repeatedly:

The storm is violent and powerful enough to overwhelm the sounds of surburban life:

Machen develops the noise of the garden gate into a symbol of his traditionalist and conservative dislike of the newly-built London suburbs. Again from The Hill of Dreams:

Lucian can try to escape what Machen later called ‘the raw London suburb and its mean limited life’ through long, digressive walks in the tangle of streets or else westwards into what might now be termed Edgelands:

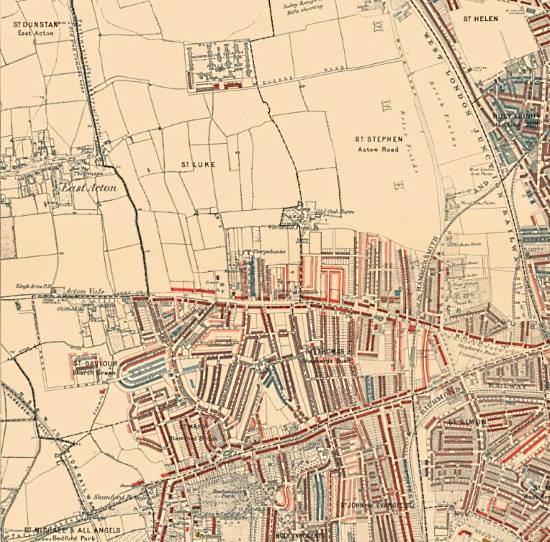

Booth’s Poverty Map, compiled towards the end of the 19th century, shows some of these west London outskirts. The triangle of Shepherd’s Bush Green lies to the lower right-hand side, with Wormwood Scrubs prison standing in isolation near the top:

But these solitary journeys only make Lucian feel more cut off from humanity – the city is for him as ‘uninhabitated as the desert’. An alternative escape route offers him the possibility of communing with others, but only through a gradual dissociation from reality. One of the most striking passages in The Hill of Dreams recasts a Saturday night, possibly in or near Shepherd’s Bush, into the bacchanalia of a witches’ sabbath ‘loud with the expectation of lust and death’:

The next day the banality of the suburb re-establishes itself through the ringing of a chapel bell (‘tang, tang, tang’) and a ‘doggerel hymn whining from some parlor, to the accompaniment of the harmonium.’ Machen intends these sounds of the growing commuter belt to represent constraints on the possible range of experience. They are set up as a surface reality to be undermined later. The Three Impostors begins with life in Red Lion Square playing out with the regularity of Gog and Magog striking the hours at St Dunstan-in-the-West in Fleet Street:

In A Fragment of Life, the City clerk Edward Darnell inhabits the ‘grey phantasmal world’ which Machen claims is most people’s lot before becoming more aware of a different reality filled with ‘grotesque and fantastic shapes, omens of confusion and disorder, threats of madness’. The routine of the commuter is represented in the conversations Darnell hears on the bus from Uxbridge Road:

The customary companions of his morning’s journey were in the seats about him; he heard the hum of their talk, as they disputed concerning politics, and the man next to him, who came from Acton, asked him what he thought of the Government now. There was a discussion, and a loud and excited one, just in front, as to whether rhubarb was a fruit or vegetable, and in his ear he heard Redman, who was a near neighbour, praising the economy of ‘the wife.’

‘I don’t know how she does it. Look here; what do you think we had yesterday? Breakfast: fish-cakes, beautifully fried—rich, you know, lots of herbs, it’s a receipt of her aunt’s; you should just taste ‘em. Coffee, bread, butter, marmalade, and, of course, all the usual etceteras. Dinner: roast beef, Yorkshire, potatoes, greens, and horse-radish sauce, plum tart, cheese. And where will you get a better dinner than that? Well, I call it wonderful, I really do.’

Although a conservative, Machen suggests that revelation is within the grasp of anyone who wants to reach for it, rather than being the preserve of an elite of adepts. Darnell, after all, belongs to the lower middle class. In The London Adventure (1924), Machen recalls how a Salvation Army funeral service in Lower Clapton had rediscovered for itself the ancient patterns of call-and-response, and so people of ‘very indifferent education’ were capable of creating a ‘remarkable and impressive’ occasion.

In Machen’s world-view, what’s old is generally good, and what’s new is usually disagreeable and inferior. Not only do the new suburbs and vast late-Victorian cemeteries obliterate the precious countryside and its half-buried hamlets and taverns, but the London of the 1920s sounds worse than that of the 1880s. From Far Off Things:

Part of Machen’s legacy is a way of writing about London by trying to re-enchant it. Few people now can summon up the same belief in the existence of a mystical reality alongside the everyday physical facts of pavements and buses. What survives into recent psychogeographical writing is the elegaic stance, the intense interest in the past, and it is significant that this has found a new resonance as London undergoes another spasm of rapid and profound change.

ADDENDUM: For a rejection of the argument that Lovecraft was influenced by Machen in his treatment of sound, see this post on the Tentaclii blog. In my opinion the parallels between sound-themes in The Three Impostors and Lovecraft’s work are too strong to be coincidental. But it is clear from the examples given on Tentaclii that Lovecraft’s use of ‘hearing without seeing’ was indeed established before he encountered Machen’s work in the early 1920s.

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology