Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

In memory of Richard Beard, wildlife recordist

I AM very sorry to report that the wildlife recordist Richard Beard died a few days ago. We first met in 2010 at the British Library Sound Archive where he was working as a part-time volunteer for the wildlife section.

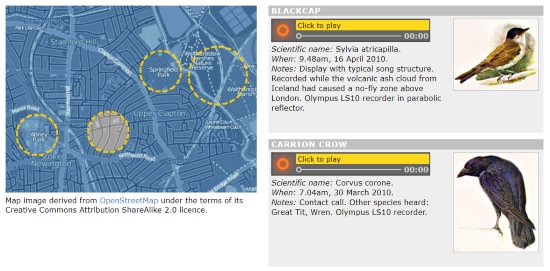

For hours at a time he’d sit in one of the Archive’s small recording studios and patiently work his way through batches of nature recordings, listening and noting. Many were ones he’d made himself, for Richard was a very knowledgeable and skilful recordist, although he wore his expertise lightly. After we got to know each other a bit better, he kindly offered to share some of his London wildlife recordings with my website. The first batch appeared here in 2012 under the title of Richard Beard’s Hackney wildlife.

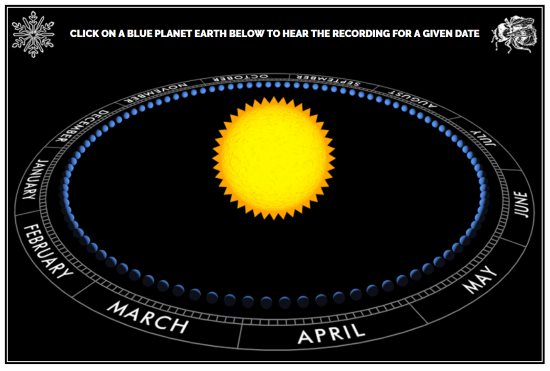

These were good recordings and Richard clearly knew a great deal about birdsong, so I was keen for him to contribute more. He mentioned something he called the ‘Breakfast Project’, which seemed to involve him recording birdsong quite early in the morning, and which at the time was a work in progress. Eventually he completed it, and offered me details of around 360 recordings, each made at 6 a.m. in his back garden and representing nearly every day of the year. I was both taken aback and excited at the scale of the task he’d accomplished.

After some head-scratching I suggested having a single webpage linking to and presenting around a hundred of his morning recordings, and the result was titled The Hackney year.

I was never entirely sure what Richard felt about this treatment of his work, and suspect it may have seemed austere compared to the experience of birdsong among hedges and garden fences, trees and bramble patches – all the living, untidy intricacies of Darwin’s ‘tangled bank’. If so, Richard was too polite and good-natured to tell me. His recordings made a very significant contribution to the London Sound Survey, and I will always be grateful for them.

What is lacking from this appreciation is a photo of Richard, and I can’t find one online. He cut a good figure of a man, looking as if he’d been keen on playing sports when he was younger, and with a broad, friendly face. He spoke with a gentle Cockney accent. I would guess Richard to have been in his late fifties when we first met, but he seemed younger because of his openness and lack of cynicism.

Richard didn’t only record in and around London, but he felt a strong connection to the green spaces of east London, in particular the Hackney and Walthamstow Marshes running alongside the river Lea. Much of this arose from his family having lived there a very long time, going back to at least the beginning of the 19th century when an ancestor had owned a farm near the Marshes, most likely keeping a herd of cattle grazing among the riverside meadows.

In later years, Richard and his wife Fern spent a lot of their time on the Isle of Wight, where Richard continued to make recordings. His death is a sad loss to wildlife sound recording in Britain and to all who knew him.

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology