Introduction • Chelsea Harbour • Mouth of the Westbourne • Custom House Stairs • Jane Parker, Wapping • Nicola White, Greenwich • The Albert Basin • Rainham, Essex • Aveley Marshes, Essex • Procter & Gamble, Thurrock • Peter Beckenham, Swanscombe • Tilbury Docks • Shornemead Fort, Kent • Coryton Refinery, Essex • Allhallows Marshes, Kent • Maplin Sands, Essex

LONDON'S RIVERS AND streams join the Thames each in their own distinctive way. Beverley Brook ends up in a dismal culvert, the Brent goes past a fascinating maze of boatyards and docks, the Fleet used to stink out Blackfriars station before it was recently rebuilt, and the Effra emerges into daylight from a box-like conduit near the MI6 building.

Two flood-gates in a slightly sinister-looking recess mark where the Westbourne trickles into the Thames at Chelsea. The floor of the recess is slippery underfoot and heavy chains hang beside each gate, as if one of Vauxhall's more esoteric nightclubs had been transplanted a short way upstream. The river has been known variously as the Kilburn, the Kelebourne, the Bayswater River, the Ranelagh River, the Serpentine River and, presumably to friends and admirers, simply the Bourne.

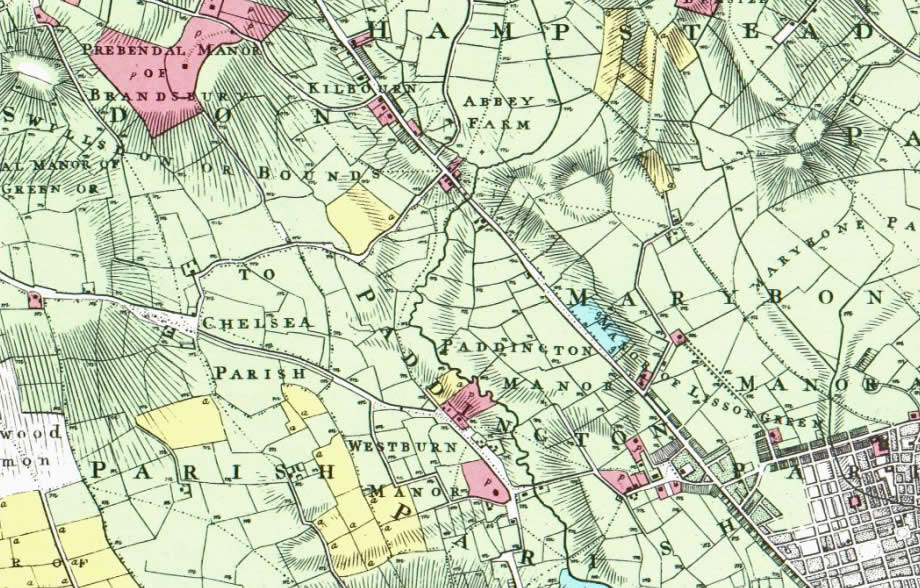

The Westbourne rises at Whitestone Pond at the southern edge of Hampstead Heath and is immediately sent underground where it continues for the whole of its course. In 1800, however, it ran above ground from Hampstead south to where it fed the Serpentine and then onto the Thames. The extract from Thomas Milne's Land Use Map of 1800 below shows the Westbourne running approximately along the centre from its source to the northern end of the Serpentine. A second stream is shown joining from the east at a confluence immediately below Abbey Farm.

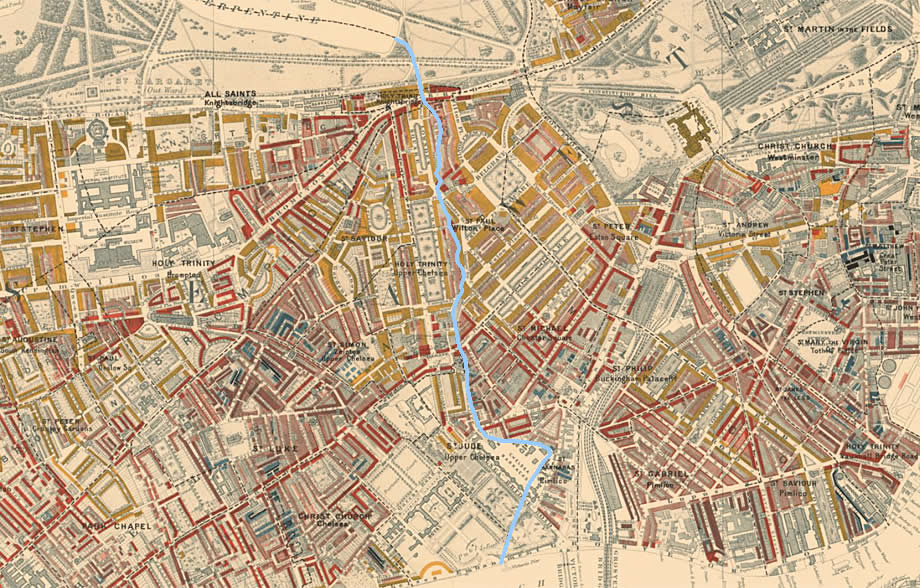

The expansion of London westwards beyond Mayfair meant that the Westbourne was conduited and then buried from the early 19th century onwards. None of it can be seen above ground in Charles Booth's Poverty Map of 1898–99. South of the Serpentine. the river had left its traces in the place name of Knightsbridge and by defining the boundaries between four parishes. I've picked out its course below in blue. To the west of the Westbourne are the parishes of Holy Trinity and St Jude, and to the east lie St Paul and St Barnabas. The function of waterways as recognised territorial boundaries is an ancient one, which is perhaps why the names of some London rivers have Celtic British origins: the Cray, the Brent, the Effra, and the Thames itself.

The Westbourne hadn't been forced very far underground. When Sloane Square station was built in 1868 in the path of the river, the easiest solution was to carry it over the platforms in a large iron pipe. This well-known feature can be seen below in the photo by Ogmios from Wikimedia Commons.

This may not be the only subterreanean waterway to leave clues as to its presence in a tube station. At Victoria station, the sound of running water emanates from beneath an iron grille set between the tracks at the east end of the District and Circle Line platforms. Perhaps this is the forgotten voice of the Tyburn or the Westbourne's tributary, the Tyburn Brook.

Introduction • Chelsea Harbour • Mouth of the Westbourne • Custom House Stairs • Jane Parker, Wapping • Nicola White, Greenwich • The Albert Basin • Rainham, Essex • Aveley Marshes, Essex • Procter & Gamble, Thurrock • Peter Beckenham, Swanscombe • Tilbury Docks • Shornemead Fort, Kent • Coryton Refinery, Essex • Allhallows Marshes, Kent • Maplin Sands, Essex