Street cries of the world

Street cries were once a popular subject of songs and literature in Britain, continental Europe and elsewhere. Each month from 2018 onwards I'll be scanning and transcribing publications to build this collection.

+ British Isles pre-19th century

− USA, Jamaica and Australia

The Cries of Philadelphia 1810

The New-York Cries, in Rhyme c. 1825

The New-York Cries in Rhyme 1836

The Boston Cries, and the Story of the Little Match-boy 1844

City Cries: Or, a Peep at Scenes in Town 1850

The Street-Cries of New York 1870

Excerpts from the Jamaica Gleaner group of newspapers 1896–1990

Street Cries of an Old Southern City 1910

Street Cries of Philadelphia 1920

Hawkers & Walkers of Early America 1927

Kingston Street Cries and Something About Their Criers 1927

Part 1 Part 2

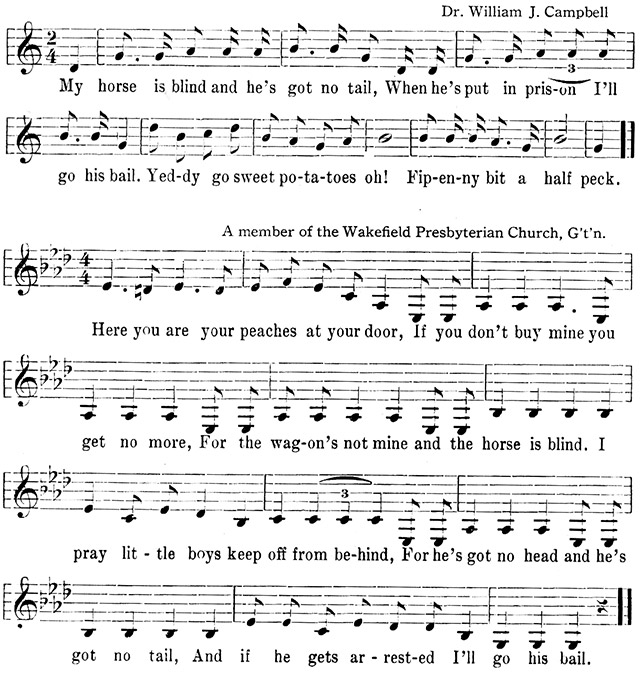

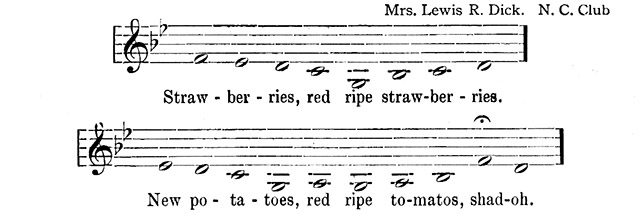

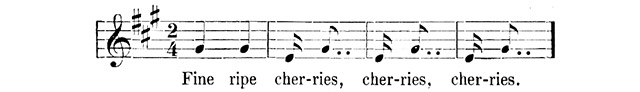

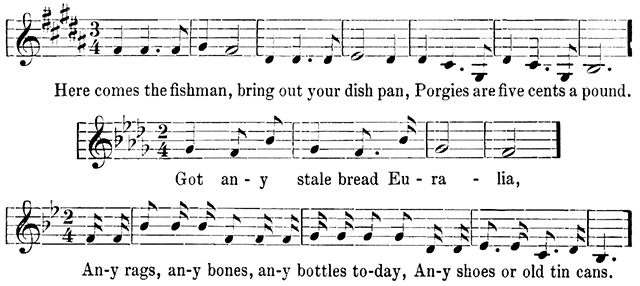

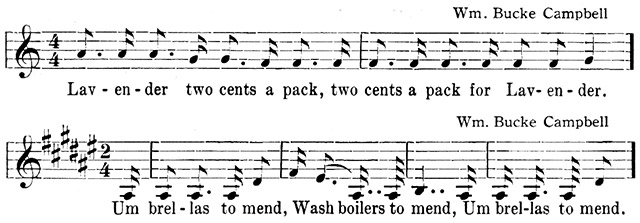

Thanks are due to members of the New Century Club, City History Society of Philadelphia, Site & Relic Society of Germantown and to many personal friends.

Some information has been found in History at your home and a little illustrated volume published in 1850, called City Cries.

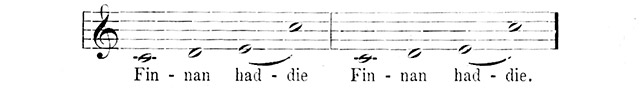

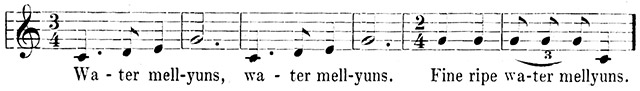

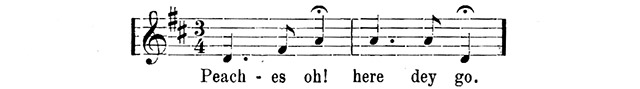

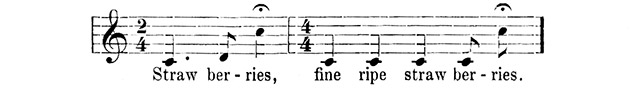

In neither of these books was there any music; this had to be taken when sung, and reduced to the staff, and the writer in this way thanks all those who helped to make this paper a success.

KATE H. ROWLAND.

STREET CRIES OF PHILADELPHIA

Any stranger who, in early times, came to this city from the country, must have been astonished at the variety of noises which assailed his ears on every side. As he grew accustomed to these noises, he realized that the cries were not only to supply the wants of the people, but served as a means of subsistence for an humble craft.

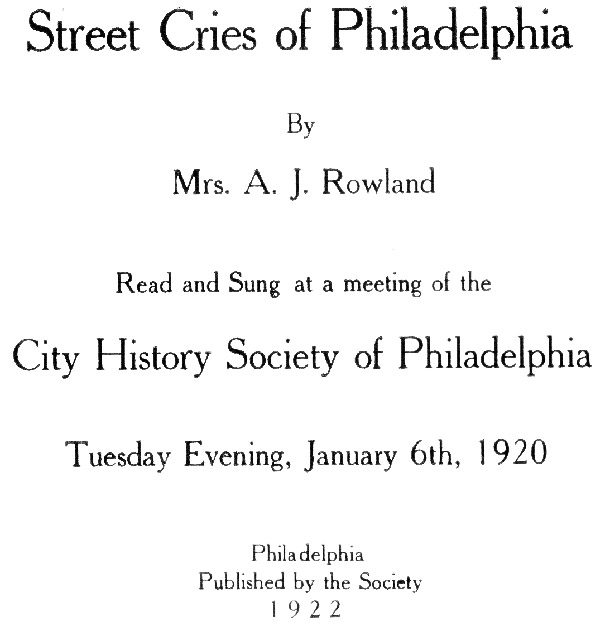

Between the years 1825 and 1835 our stranger would be startled by the blasts of a horn followed by an effort at vocal music in which these words might be heard:

“Charcoal by the bushel,

Charcoal by the peck.

Charcoal by the frying pan,

Or any way you lek.”

Looking out he would see Jimmy Charcoal, the New Jersey man, sitting on his long narrow wagon, all grimy with the dust of his merchandise, yet looking out with a bright eye for the housemaids who hastened to the door at the well-known sound of the horn.

The blowing of the horn became such a nuisance that it was prohibited by the City Councils, an action largely due to the influence of a prominent citizen, Paul Beck, of Shot Tower fame. As Charcoal Jimmy persisted in blowing his horn, he was arrested and fined. How should he announce his approach? Then a happy thought came into his mind, but he kept his own counsel. The next day the loud ringing of a bell brought many to the windows and front doors, and there was Jimmy on his wagon with the high sides. He was wearing his blue and white checked apron and he alternated the ringing of the bell with an improved version of his song:

“Charcoal by the bushel,

Charcoal by the peck.

Charcoal by the frying pan,

In spite of Paul Beck.”

So Jimmy went on his way peacefully. The only call we could find was the following:

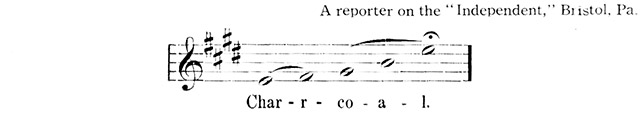

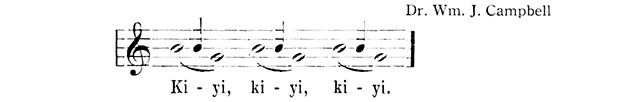

Sometimes our stranger would be wakened by a peculiar sound which surprised and puzzled him. It was the shrill piercing voice of a child singing at the utmost stretch of his power a wild sort of song — the cry of the Chimney Sweep.

There was, in the memory of some, an old, tall, nearly blind negro, who walked with a cane and worse the greenest of green spectacles. He was led by the hand by a small boy while another boy walked on his other side. Each boy carried over his shoulder a bag to hold soot. As they walked along the boys shouted at intervals of about half a minute the following cry:

The small boys employed in this way were greatly to be pitied, being bound to their masters when almost infants, and compelled to climb the flues of chimneys, scraping off the soot and carrying it away. It impaired their health and broke their constitutions.

Here is another chimney sweep cry:

Both of these cries are difficult to reduce to the staff.

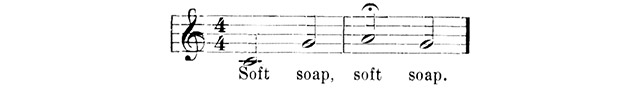

In the street below, as if to remind the sweep that he would need a good scrubbing when he comes down from the flue, comes the melodious cry of:

As the colored man looks up he would see the grinning little black face with the dazzling teeth and merry eyes peeping from the chimney.

Again would he sing soft soap and then with a nod he would trundle away his wheelbarrow, on which stood his heavy barrels of soft soap.

Then would come the brick dust vender, generally an old negro man or woman, carrying poised on the head a small tub of finely powdered salmon brick, used in cleaning knives.

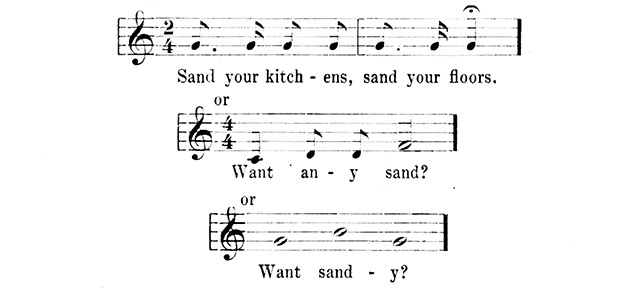

A frequent companion to the brick dust man was the sand man, whose melancholy voice invited you to

Then comes the trim baker, his head and coat collar as finely powdered as those of the most fashionable gentleman. He carried his covered basket of fresh loaves or pushed a hand-cart from door to door.

Then the aristocratic milkman rattle past in his light wagon, the bright cedar churns with hoops of shining brass standing by his side. Sometimes he rang a bell, at other times he whistled. There were also milkstands in the market.

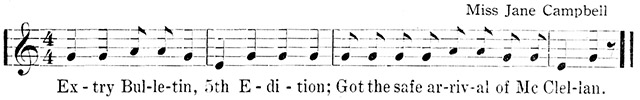

Then, too, were the noisy little urchins who collected around the doors of the printing offices, and when they had received their supply of paper dispersed through the city bawling with all their strength: “Extry Ledger! Extry Times! Extry News! Great victory. Ten thousands Mexicans killed. Santy Anna’s captured. Have an Extry, Mister? Great news.”

Here’s another call of a newsboy:

“Extra Bulletin, double sheet,

Another great battle in Market street,

A man fell over a three-cent piece

And stuck his nose in a pot of grease.”

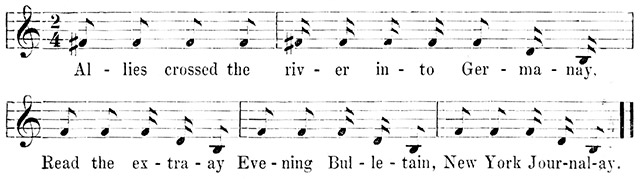

While waiting for a car (a few days ago) a newsboy bawled out the following:

Civil War news boy cry:

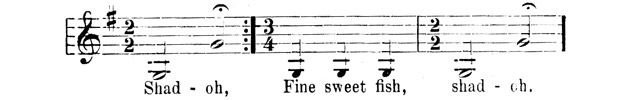

The shad season began in the latter part of March, and shortly after the fish made their appearance in our rivers, the shad women began their perambulations and cries.

A handkerchief was tied around the head and on it was a large round shallow basket with the shad.

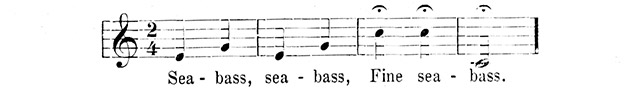

Following the shad came the call of other fish women:

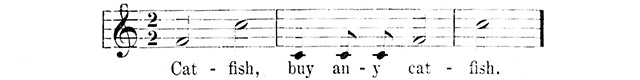

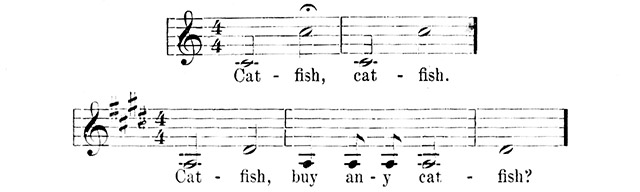

The shrill cry of the catfish woman has wakened many a person.

In one section of the city were two women who always went together. One had a high soprano voice, the other a deeper voice. They usually followed each other in their calls.

One woman while telling her impressions of her first visit to Philadelphia said that she was awakened in the morning by a shrill piercing cry.

As the days went by fruits and vegetables were called in swift succession, much to the disgust of the regular hawkers who carted their good around in a more silent manner.

Can you see in your mind’s eye, a big unshapely, uncorseted woman, with bulgy puffy cheeks, sleeves rolled up above her elbows, and a big waist apron, a padded turban on her head and on that a rectangular tray, and in her hand an empty one?

There are two curious calls that are quite interesting. The first was heard about 1859.

The next call includes several vegetables and in shad season the man always included the shad at the end of his call.

Here comes another fat unwieldy woman and she is crying with great vigor and perseverance.

Now we see a more dainty woman with trim, tight-fitting round-necked dress, full skirt and apron, an oval basket on her right arm and a large tray on her head.

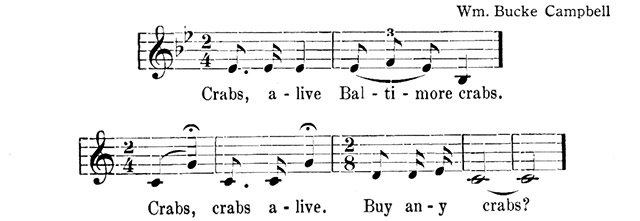

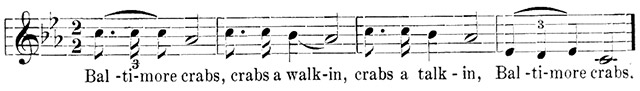

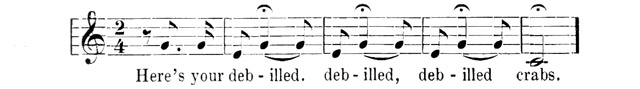

A member of the City History Society, Mr. Wm. Bucke Campbell, contributes the following:

There are not many people who dislike crabs and many were the cries that announced the crab man. Baltimore crabs were supposed to be specially delicious.

This was sung many years ago by a colored man pushing a two-wheeled cart. In a volume published in 1850 is a picture of such a cart, and of a boy who thought he would steal a crab. You can imagine the result. The crab caught his finger and the boy was almost doubled up trying to shake it off and the colored man was delighted.

Many years ago there was a kinky gray-haired colored man who used to come around periodically and in a strong musical voice sing his wares. He wore a checked gingham apron, and in the basket on his arm were delicious hot deviled crabs and it was a joy to hear him sing.

The tune of the following must have been interesting:

Crabs, fresh crabs,

Fresh Baltimore crabs,

Put them in the pot

With the lid on top,

Fresh Baltimore crabs.

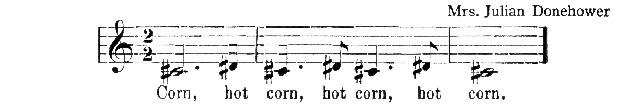

This was cried by a man who sat usually at the end of the market sheds when the markets were in the center of the streets. They were the freshly pulled ears of corn, boiled and served hot, which were kept so by being wrapped in clean napkins.

Sometimes the corn was cried by a woman who had a turban on her head, a striped shawl pinned around her shoulders and her two wooden buckets in her hands.

Next we see a colored man with a wooden pail in his right hand and a long-handled brush on his left shoulder, and he has on a swallow-tailed coat:

“Here’s the white whitey wash,

Brown whitey wash,

Yellow whitey wash,

Green whitey wash,

Wash? Wash?”

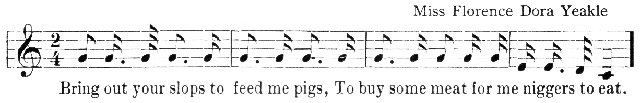

Or it may have been a musical garbage man who sang this aesthetic cry:

Sometimes the unwary stranger would be startled by the sudden shooting of a cord of wood on the cobble stones. The rasping sound of the hand saw would be interrupted by “Way-piles.” This was to warn his companion in the cellar that another armful of sawed sticks was ready.

Sometimes a brawny fellow would walk along with a huge axe over his shoulder and from the axe hung two iron wedges which jingled and made a ringing sound at each motion. But notwithstanding this he would bellow out “Split wood,” thereby revealing his professional character.

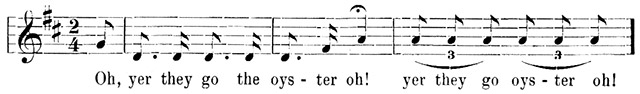

Now comes the vender of that delectable shell fish, the oyster. There was a time when there was only one oyster seller in the city who conveyed his small stock from house to house in a wheel barrow to which he had ingeniously attached a small table with its modest furniture consisting of a small tin plate, some forks, a vinegar cruet, a salt cellar and a pepper box. He would stop when called, spread his table, open the half dozen oysters and the customer would eat them in the open air, and this was his cry:

Part 1 Part 2