Street cries of the world

Street cries were once a popular subject of songs and literature in Britain, continental Europe and elsewhere. Each month from 2018 onwards I'll be scanning and transcribing publications to build this collection.

+ British Isles pre-19th century

− USA, Jamaica and Australia

The Cries of Philadelphia 1810

The New-York Cries, in Rhyme c. 1825

The New-York Cries in Rhyme 1836

The Boston Cries, and the Story of the Little Match-boy 1844

City Cries: Or, a Peep at Scenes in Town 1850

The Street-Cries of New York 1870

Excerpts from the Jamaica Gleaner group of newspapers 1896–1990

Street Cries of an Old Southern City 1910

Street Cries of Philadelphia 1920

Hawkers & Walkers of Early America 1927

Kingston Street Cries and Something About Their Criers 1927

STREET CRIES OF AN OLD SOUTHERN CITY

BY

HARRIETTE KERSHAW LEIDING

WITH

Music and Illustrations

CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA.

1910

THE streets of this quaint, old Southern City are teeming with sights and sounds of interest to those in whom Familiarity has not “bred contempt.” To a stranger nothing is so amusing or unintelligible as the various cries of the hucksters as they ply their street trade, endeavouring to inform the “world and his wife” concerning their wares. To an inhabitant of this enchanted old “City by the Sea,” numerous members of this “Brotherhood of the streets,” become well-known friends; their several cries, familiar music.

When asked about themselves these hucksters tell you that they come “From up de road” or “Across from Jeems Island, Mam” and some from “ober de new bridge” and still others again are town negroes who secure their wares “Down at Cantini Wharf and Tradd Street Breakwater, my missis.”

They congregate there to receive the boat loads of fresh “Vegetubble” and “Swimpy, raw raw.” Long before even these enterprising denizens of the sleepy town are up and doing, the “Mosquito Fleet” has put to sea while the still, grey dawn is breaking and you hear them sending back in calm weather the long, faint cadence of a rowing song:

“Rosy am a handsome gal!

Haul away Rosy – Haul away gal

Fancy slippers and fancy shawl!

Haul away Rosy, Haul – away

Rosy gwine ter de fancy ball!

Haul away Rosy – haul away gal.”

Even in wet or windy weather when the wind is fresh and strong, sails are hoisted and silently the fishing fleet flits out like a flock of ghostly birds across the harbor, across the bar and out to the fishing banks, forty miles away. For these fishing boats are manned by intrepid sailors known far and wide for skill and daring.

All of the folk songs have a queer minor catch in them and even the street cries have an echo of sadness in their closing cadence. Early one morning the usual shrimp “Fiend’s” cry of

was superceded by a strange, unfamiliar, and piercing sweet cry in a boy’s faint, clear soprano. Like a little lark this “Jean De Reszke” of the small, black world, gave his name and advertised his wares, in a voice that made you think of the freshness of dawn across dewy fields. He stood under the window and sung:

The shrimp are sold early in the morning. When the “Mosquito fleet” puts back into port, the fish are hawked about the streets and the lusty-lunged fishermen cry then

with an ominous voice, that seems to hold in its queer, breaking sound a reminder of the days and nights of danger which falls to the daily lot of these toilers of the deep who still must put out to sea in calm or storm alike, regardless of the death which threatens when “The Harbor bar be Moaning.”

All is not sadness, for here and there a quaint bit of human nature of glint og humor, shows. For instance, even in the Street cry parlance, “The Sex” holds its wonted superiority and you will find that “She Crabs,” called through the nose of the vender, “She Craib, She Craib” bring more money than just ordinary “Raw Crabs” – by which distinguished title is meant the less desirable male crab.

“Old Joe Cole, good old soul,” who does a thriving business in lower King Street under the quaint sign of “Joe Cole & Wife” is the bright, particular, tho fast-waning, star of our galaxy of street artists. He sets the fashion, so to speak, in “hucksterdom.” Joe has many imitators but no equals, for he looks like an Indian Chief, walks with a limp that would “do a general proud,” and uses his walking stick as a baton, while bellowing like the “Bull of Bashan.” It is a never-to-be-forgotten occasion when Joe lustily yells:

“Old Joe Cole – Good old Soul

Porgy in the Summer-time

An e Whiting in the Spring

8 upon a string.

Don’t be late I’m watin at de gate

Don’t be mad – Here’s your shad

Old Joe Cole – Good Old Soul.”

Porgy, it may be remarked in passing, is a much prized variety of chub, and is much esteemed among the colored brethren, “embracin of the sisterin,” as one old, colored preacher said.

When asked to sing so that his remarkable cry might be correctly reproduced, Joe gravely informed the awe-struck crowd surrounding him, “Yunna niggers gwan from here now cos little Miss done ax me to sing in de megafone so as she can write Me down in de white folks’ book and she aint ax none ob yunna niggers to do dat ting, jest Me.” And sure enough I did.

The “Vegetubble” Maumas are wonderful wide-chested, big-hipped specimens of womanhood that balance a fifty pound basket of vegetables on their heads and ever and anon cry their goods with as much ease and grace as a society lady wears her “Merry Widow” hat and carries on a conversation. As these splendid, black Hebes come along with a firm, swinging stride you may hear:

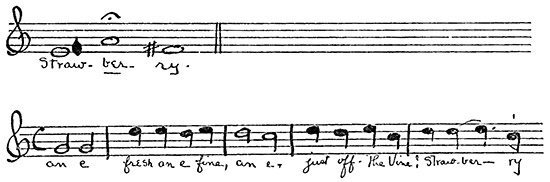

Perhaps it will vary in season to “Strawberry.” While the masculine rendition of “Strawberry” is put in the following enticing form

Or may be that yet again you will be informed that “Sweet Pete ate her.” Which being interpreted means that they are selling sweet potatoes to the tune of Red Rose Tomatoes, only it sound quite cannibalistic sung this-wise.

Amongst all this babble of femininity the masculine call of “Little John,” as he styles himself, comes as a relief to the ear. He sings as he wends his way: “Here’s your ‘Little John’ Mam. I got Hoppen John Peas Mam! I got cabbage – I got yaller turnips Mam, Oh yes Mam” – and so he comes and you buy what you want and on he goes still singing what he’s “got” to sell. “I got sweet Petater – I got beets; I got Spinach;” and so on like the brook, forever “Little John sings, his approached marked by the musical sign “Crescendo” his retreat by “Diminuendo.”

When I hear “Little John,” I think of an old street crier, long since dead and gone, whose cry was used to advertise his load of water-melons, thusly:

Load my Gun

Wid Sweet Sugar Plum

An Shoot dem nung gal

One by one

Barder lingo

Water-millon.

Now – a “nung gal” is “Darkese” for young girl, as you will find out when you get a plantation darkey to tell you the ancient rhyme of the love affair of the old Oyster Opener and the Young Girl.

His tragic affair of the heart is briefly told in the dialogue which follows: The Old Oyster Opener taking the part of “Ber Rabbit.” “Ber Rabbit what you de do day?” or as we would say “Ber Rabbit what are you doing there?” and “Ber Rabbit” sadly answers – “I open de oyster for nung gal. Oyster he bite off ma finger an Nung girl he tek me for laugh at.”

It is a curious fact that the Island negroes make no distinction in talking, between “he and she” and when “Ber Rabbit” of the above says “Young gal He take me to laugh at,” the old man gives a good illustration of that peculiar trait of their language.

There is a gentle looking old woman who gives vent to the most ferocious and nasal howl of – “come on chillins and get yer monkey meat.”

Should you hear it, do not be alarmed for it heralds nothing worse than a harmless, old body selling the children’s favorite cocoanut and molasses candy.

This performance is only equalled by the one of the mild, antediluvian “Daddy” who gravely thrusts his wooly head into your back-gate and emits in an eminently respectful tone of voice the following jargon:

“Enny Yad aigs terday my Miss” which being interpreted means – “Do you wish any eggs which my hens have laid in my yard and which therefore are fresh eggs Q.E.D. Fresh Yard Eggs.

In Charleston, even the chimney-sweeps are musical, and as their tiny faces appear at the top of the chimney they are sweeping, you hear “Roo roo” sung out over the sounds of the street below.

Also to this tribe the charcoal boy belongs. He drives into town a tiny donkey hitched to a tiny, two-wheeled cart. The cart and load are black, the donkey is black, the boy is black and the only other color that you can see in the whole outfit is the whites of the boy’s eyes as he rolls them around and calls the eerie, long-drawn-out “Char—coal.” He sounds weird, melancholy and even doomed, with his mournful cry of “char-coal.” You wonder which is the saddest and blackest: the driver, the driven, cart or contents, as they wend their solitary and spooky way onward, crying ever that sad minor wail of

All these interesting things and more too are here, jostling your elbow, passing your window, begging your custom and offering rich and picturesque effects to those who “Eyes to see,” and furnishing a queer, original but fast fading, street symphony to those who have “Ears to hear.”