Street cries of the world

Street cries were once a popular subject of songs and literature in Britain, continental Europe and elsewhere. Each month from 2018 onwards I'll be scanning and transcribing publications to build this collection.

+ British Isles pre-19th century

− USA, Jamaica and Australia

The Cries of Philadelphia 1810

The New-York Cries, in Rhyme c. 1825

The New-York Cries in Rhyme 1836

The Boston Cries, and the Story of the Little Match-boy 1844

City Cries: Or, a Peep at Scenes in Town 1850

The Street-Cries of New York 1870

Excerpts from the Jamaica Gleaner group of newspapers 1896–1990

Street Cries of an Old Southern City 1910

Street Cries of Philadelphia 1920

Hawkers & Walkers of Early America 1927

Kingston Street Cries and Something About Their Criers 1927

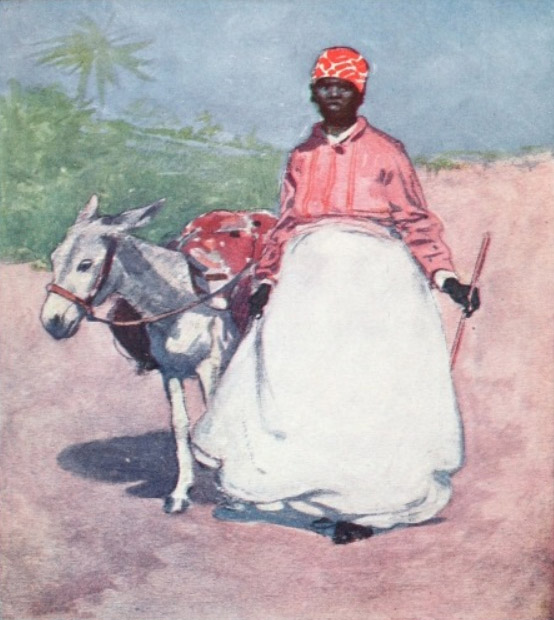

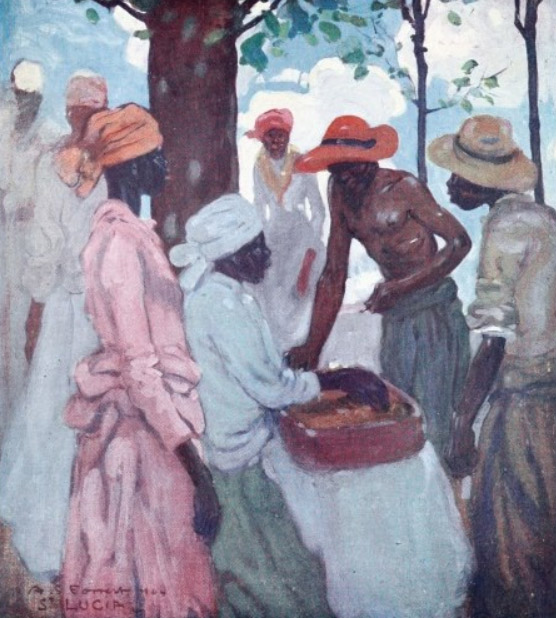

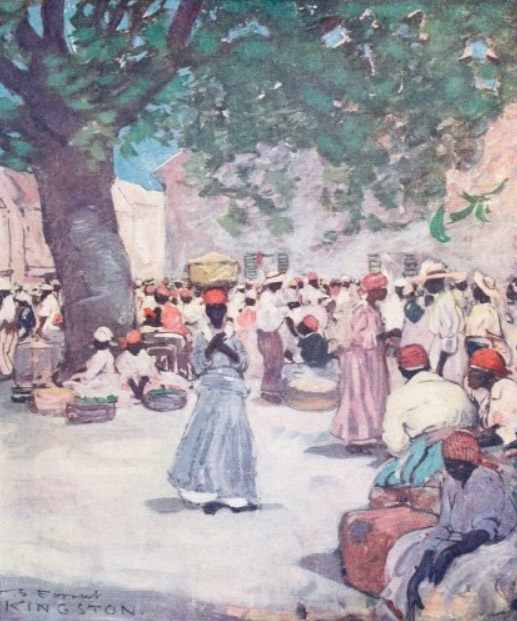

The following excerpts appeared variously in the Daily Gleaner, Kingston Gleaner and Sunday Gleaner newspapers published in Jamaica. The paintings are by A. S. Forrest from John Henderson’s book The West Indies, published in London in 1905.

MONDAY, JULY 27, 1896

The Noise Nuisance

Several complaints have reached us recently and have been duly inserted in our columns – regarding the disturbances caused in the city by dogs and by the no less disagreeable brawling of unruly men and women. This is an old complaint and we have written on the subject again and again. We confess we have no hope of a remedy being devised and introduced in the interests of citizens with sensibilities. Public spirit is at too low an ebb to effect any change; the general idea of personal freedom is too broad to be easily narrowed; the law is inadequate to deal with the matter; and even if it were adequate it is perfectly out of the question to make the Police comprehend the situation. The dog nuisance is one about which every visitor to the island complains. The city at night is a camp of yelping curs. One wonders how their owners continue to be indifferent to the noise or to sleep soundly through it all. It is said that the higher the human race develops the more acute its sensibilities become. Here, perhaps, lies an explanation of the deadness to exasperating sounds displayed by the aforesaid owners. In such a case it is hopeless to expect that anything can be done for a few generations yet. The same remark applies to the Police. Tell a constable that you cannot obtain your rest for the barking of dogs the livelong night or the howling of a few irresponsible persons in a yard close by and he is unable to understand the ground of the complaint. He will probably reply that the dogs are barking at “duppies” and must not be meddled with and that the persons who are howling are simply enjoying themselves or telling you, musically, what is in the hymnal. This inability to conceive what the nuisance consists in is the greatest obstacle in the way of remedial regulation. If the Police were doing their duty by the dogs there might be some improvement. An unlicensed dog has no legal right in the city. His proper destination is Sutton Street and his proper diet is the small powder given by the Police. It has been well said that a well-bred dog is a better companion than many a man, but the majority of the dogs in the city are objects which a well-bred animal would utterly repudiate and neither they nor their owners should be shown any mercy.

For some time a lively discussion has been going on the Times on a similar topic. Most towns in England, Scotland, and elsewhere have rigid rules regarding such noises as those complained of in Kingston, and the streets at night in these places are absolutely still. It is often remarked by colonists on first returning home that the nights are very quiet. The recent discussion has been concerning what might be termed a ‘higher-class’ series of noises – that caused by itinerant musicians, distributors of circulars, trade cries, &c. The discussion was not likely to escape the notice of the London County Council – that body took up the matter have made an exhaustive enquiry, also obtaining counsel’s opinion as to whether the Council could make bye-laws for controlling street music or street cries and noises. Counsel advised that the existing laws cover the street music nuisance, and with reference to street cries or noises other than street music he thought that of all the suggested bye-laws which had been submitted to the Council the only one which could be made by the Council would be those to prohibit loud and persistent shouting for the sale of goods or for the distribution of circulars or knocking or ringing at houses from door to door, or the keeping of any animal which should be a nuisance to the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, or keeping or using a shooting gallery, steam roundabout, steam organ, or other like thing within a certain number of feet of any street. The committee who have the matter in hand state that the main desire of those who have approached the Council on the subject is to obtain some enactment under which the police or an officer of the Council might take cognizance of street music or noises without prior complaint in each specific case by some person who was annoyed by the act but as their power to do so is limited they propose that fresh legislation should be provided as the best remedy. This is how they manage things in London.

A similar complaint is meantime being ventilated in New York. The Herald the other day devoted its leading article to the subject, and half-humorously, half-seriously, pointed out the grave nature of the situation. It admitted that there are the absolutely necessary sounds, the “clatter of street cars and the jingle of their bells, the rumbling of other vehicles and the staccato accompaniment of the horses’ hoof beats on the pavement; while in water bordered localities there comes the distant roar of ferry-boat whistles and oft-times fog signals. Such noises cannot well be prevented, and persons whose nerves will not permit them to rest and sleep within range of these disturbances must perforce retire from city life.” But many other noises are permitted – and it is against the unnecessary nuisances that, the Herald says, the average citizen has a right to protest. It mentions them in detail. “There are factory whistles that are sounded at seven o’clock every morning and at intervals through the day; there are railway locomotives whose screeching and snorting are so provocative of insanity and incentive to murder; there are hand organs of high and low degree, with occasional street band accompaniments; there are howling curs and snarling cats; there are ponderous loads of iron that play a devil’s tattoo over the Belgian block or granite pavements, and finally there are mobs of discordant pedlers whose harsh and unintelligible cries recall Scott’s description of the wild rush of Roderick Dhu’s clansmen in the Trossach’s jaws, amid such a tumult as if ‘all the fiends from heaven that fell had pealed the banner cry of hell.’ ” As for “the barking dog and the crying cat they should be sent to the country or to the river.” Even church bells find little favour in New York as they do with some people in Kingston as our columns have testified. There has been some complaint of these as adding to the already superfluous noises of New York, and letters have been published attacking and defending them. The complainants in one case were denounced as having no music in their souls and as being incapable of recognising the difference between a set of chimes and a melodious peal of bells. Probably the people disturbed felt the need of sleep more than of music in any form, and perhaps, therefore, they may be pardoned for not having drawn a nice distinction between the kinds of sound. If it kept them awake, says the Herald, they were right in making a protest against its continuance. New York, like Kingston, wants a little of German spirit infused into its municipal life. As long as the present apathy exists and right of the individual are subordinated to the might of the multitude we shall obtain no respite from the nuisances complained of.

SATURDAY, JULY 24, 1897

“Pity the Poo’ Blin’, Massa!”

Old Father Kane interviewed. Thirty-one years in darkness.

The “Silly season” had set in, in earnest; the Legislative Council has been prorogued some days previously. The Royal Commssion on sugar had concluded its sittings, and things all along the line were dull in the local newspaper world.

This was the state of affairs when one morning I came across “Old Father Kane.”

Perhaps there are not many readers of the Gleaner who can claim acquaintance with the individual in question, but his figure must be familiar to most residents in Kingston, and there are few who have not from time to time heard the plaintive appeal of “Pity the Poo’ Blin’, Massa and Sweet Missis” – for it is one of the street cries that has been heard in the city almost daily, Sundays excepted, for years past.

As the old blind man was walking down East Street one morning, led by the hand by a bright looking little boy of six or seven, I did not hesitate to accost him and ask if he would allow me to pay him a visit with the object of learning something of his past history, as I was interested in him as being a well-known character in the city.

Permission was readily accorded me and the other morning I called at the address given, a respectable little house in James Street.

Rapping at the side gate, my summons for admission was replied to by a neatly dressed little girl, evidently just about leaving for school, as she wore a jaunty little straw hat and carried a slate and some books.

“Oh! it’s Father Kane you want Sir. Come in,” and she led me to the yard at the back of the premises where I found the old man seated on an empty kerosine tin, nursing a child of two or three years of age whilst another a little older was playing about his knees.

The moment I spoke to him he recognised my voice and at once proceeded to converse with me as he heartily enjoyed having the opportunity of telling a stranger something about himself. I will repeat his conversation very much in his own words, but avoiding the vernacular.

“Yes Sir,” he said, “they all call me ‘Old Father Kane’ and, as you see, the children are fond of their ‘Dadda.’ I was born a slave on a large property, in the Port Royal Mountains eleven years before ‘Freedom’ – which was in ’38, so that I am now seventy-one years of age though I do not feel like it, for, thank God, if it were not for my terrible affliction I have not much to complain about, for my health has been good for many years, and people are all kind to me. [As a fact “Father Kane” does not look much more than five and fifty.] My father was a freeman but my mother was a slave and almost as far back as I can remember I was employed in doing all sorts of odd jobs about the estate.”

“Were you well fed?”

“Oh! yes, plenty of rice, peas, yam, plantain and banana, with sometimes salt fish and beef. I was not blind then, not till forty years after that did my life become all black, black as you see,” and he turned his sightless eyes upwards, showing the bloodshot optics from which all traces of pupils had disappeared.

“There was no education in those days,” he continued, “but otherwise we were well cared for and as soon as I was free, I got employment upon the estate until one night thirty-one years ago, almost to a day, I went to bed as usual, except that I felt some queer pain about my body – it was a kind of itching sensation, like the prickly heat, but I did not take much notice of it.

“Just as I was falling off to sleep I felt a strange pain at the back of my eyes and a sensation as if some one had thrown water in my face. All became dark, although just before the moonlight had been streaming into the room.

“Putting my hand to my face I found water was running out of my eyes, and called out for help!

“A woman came running in and shrieked as she was me sitting on the bed, calling out “Mass Kane, Mass Kane, him eye-balls bus’ ” is true.

“From that day to this I have been totally blind. I was taken to the hospital the next day and remained there for some time, but never have I seen a ray of light since. They said I was suffering from blood poisoning and I believe it was true for before I left the hospital my toenails and fingernails fell off. I have not been able to do a day;s work ever since, but I have never asked for single [?] from the Government.”

“Are you married?”

“Forty years ago, and I have had several children and my wife is alive now but she is bed-ridden and lives in the country. The people are all very good to me here” – he added waving his hand around the yard, “and I have several little god-children who take turns in leading me about, especially on Saturday when they are not at school. They read to me too, and they are all kind, yes, very kind to the poor blind man.”

I felt I was treading on somewhat delicate ground by my next question, but I asked “Do you make much in the way of what charitable people give you? I have heard that is customary here for some well-to-do persons to give a small amount weekly to the poor?”

“Yes,” he replied, “that is true, but if I apply for it my turn always comes last for in a crowd of people who are hungry there is not much sympathy with a blind man, and he has to take his chance. Besides it is not every day that I can get one of my god-children to go out with me, but I do not complain, the Kingston people are kind, yes, very kind,” he repeated.

“Have you ever tried to do any work, basket work, for instance?”

“See my hands,” the old fellow answered, “the nails keep falling off, and I cannot feel with the tips of my fingers.”

As I was leaving I asked “Old Father Kane” is he had never tried the experiment of being led about by a dog, to which he replied that he had done so some years ago, but one day his dog got out into the street where it fell into the hands of the dog catcher, and as he had not the money to get it back, the unfortunate animal was poisoned.

THURSDAY, MAY 9, 1901

Booby eggs are in season, and throughout the streets of Kingston may be heard the dismal whine of the vendor: “Boobiyegg! Boobiyegg!” In spite of the note of misery in the street-cries of Kingston, they have a charm which only those who love our island can appreciate. At a hotel in a great American city, a Jamaican gentleman once heard an actress describing her experiences during a week spent in “an island called Jamaica.” Our fellow-countryman did not catch the first part of her narrative, but his heart bounded over many miles of land and sea when he heard a perfect imitation of that familiar cry: “Ripe mango gwine pass!” His feelings at hearing this echo of the old days may be better imagined than described.

FRIDAY, JULY 16, 1915

Interesting Lecture

The Wesley Guild, in connection with Wesley Church, was treated to a lecture on Wednesday night last by Mr. Astley Clerk on “Street Cries and the Criers.” Whilst the lecturer was interesting and humorous at the same time, he was instructive. In speaking about the “cries” he, in some instances, compared the musical cries which were heard in former years with the deteriorated cries heard at the present time, and one could not help thinking that it is just as well, if street cries must be, if they are necessary to the prosperity of the vendors that they should be musical. Speaking about the “criers” themselves the lecturer made his audience feel that in many instances they were some of our hardest toilers who deserved to earn every penny they got. He spoke of the hard work that is lost sight of. Many toil all night so as to be in good time early in the morning at our doors with produce, fowls, fish, starch and other commodities. We could wish that some day this lecture could be given to the public in permanent form. There was a large audience, and it was delighted. Mr. Astley Clerk can be sure of a full house when he appears again. Mr. W. Brown’s solo “The Toilers,” was much appreciated.

SATURDAY, JULY 18, 1931

A South African woman recalls a visit to Jamaica – island of pirate legends

By Emily B. Hewat

[. . .] The cheery, laughing, care-free Jamaicans reminded me of our own happy coloured folk. And as in the old days of Cape Town the Malaya and coloured folk hawked round fruit, and vegetables with their quaint cries, blew their fish-horns and cried their “pengwinney eggs” for penguin eggs so the Jamaicans also have their quaint street cries.

As they go round with hot pies for sale on large trays or in baskets they call “Haat patties an cruss” which sounds far more temping to eat. And just as negroes have a peculiar use of the word “No” so you hear the Jamaicans calling “No wine pine, no ale pine, no soda water bottles?” which really means “Any wine pints, any ale pints, any soda water bottles?”

MONDAY, DECEMBER 13, 1937

Pleasant Local Customs

“Don’t even kill the crowing cocks.”

Sir, – As a visitor who dearly loves Jamaica, let me express my gratitude to the Cudjoe Minstrels, the group of young folk-lore enthusiasts who are collecting the old Island songs and singing them with so much freshness and zest. Their particular contribution to the fun of life I could find nowhere but here, because they tap the uniquely Jamaican sources of beauty and laughter. [. . .]

A subtler memory, which haunts me when I am away from the island, and makes me pine to return, is that of your plaintive street cries. After a week or two in Kingston I feel I personally know these faithful and laborious vendors though, as a hotel guest, I give them no direct custom. There is one after-dusk passer-by in whom I take a special interest. It is always the same old riddle in my mind: has she really tramped the streets all day, in vain; or did she have a good sound afternoon’s nap, and then, fresh as a daisy, start out with the lamp-lighter, when she could play most artfully on the heartstrings of the charitable?

I have been told there is some thought of discouraging this street music. I sincerely hope the movement will wither before it has time to do any harm. We Americans come to Jamaica not because it is “as good as Florida” or “better than Florida,” but because it is different, and we like its character. Climate is not everything. Good beaches we have at home in illimitable miles of white hard sand. [. . .]

I am, etc.,

GLANVILLE SMITH

South Camp Road Hotel,

Kingston,

December 7, 1937.

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 1938

Jamaica Evening at the Ormsby Hall

“Pepperpot” in aid of Library funds will include native songs and dances in costume

[. . .] Another item that will interest the public is the Annancy Story which will be told by Miss Rhodd. The Y.M.C.A. orchestra, under the direction of Mr. Neilson, will play a medley of Jamaican tunes, the Cudjoe Minstrels will sing, Sam and Slim will render native songs of today, and Mr. Easton Soutar’s choir will sing negro spirituals; and between some items, the inimitable Bobby Burns will show us what Jamaican street cries sound like, “Fresh Fe-eesh, Fresh Fe-eesh.”

The entertainment is in aid of the Library Funds of St. Andrew High School, St. Hugh’s and Wolmer’s Boys School.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1938

‘Jamaica Tropic Isle’ featured in the ‘Spanish American’

“Jamaica, Tropic Isle!” This is the lone feature of a 4-page illustrated booklet entitled “The Spanish American,” published by Grace Line, New York, and distributed to travellers on their chain of ‘Santa’ steamers. [. . .]

Kingston is described in these words: “Capital city of Jamaica since 1872. Population 120,000; second wealthiest and important city of the entire West Indies. It has emerged from fires and earthquakes with wide thoroughfares and imposing buildings.

“Its street cries will hold Kingston in your memory long after your visit. They are strange, shrill, and faithfully typical. The intonations have not changed since the infancy of the oldest inhabitants. Peanuts, coconuts, ices and pinir, uttered in a dancing sing-song.”

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 1938

Packed audience applauds Cudjoe Minstrels’ triumph

Commissioners see lighter and brighter side of a Jamaica labourer’s life

His Excellency the Governor and Party and Members of the Royal }Commission had a most enjoyable introduction to the music and spirit of Jamaica, when, as members of a completely packed house, they attended the Cudjoe Minstrels programme at the St. George’s Church Hall on Saturday night. [. . .]

The programme was well laid out, the groups of songs by the Minstrels being intermixed with assorted trivia such as the street cries of our hawkers and pedlars. The back drop curtain was a most appropriate one. It represented a typical ‘cheapside’ section, with amusing signs such as “In God we trust. Others cash”, “Sanitary drinks” and the ubiquitous pictorial boot and shoe makers shingle.

The street preaching meeting which was staged was, to a great degree, faithful in its reproduction, but it lacked some of the vigour associated with these meetings. Orthodox clergymen certainly would have very little cause to complain to the Royal Commission about such gatherings.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 27, 1940

Round and about people and places

The week’s talk has, of course been about the Segovia recital at the Ward Theatre, last Saturday night. [. . .]

Talking of noise, there was plenty of that to disturb both performer and audience. Street cries, horns hooting, burring and buzzing inside and the rest of it, annoyed sensitive listeners. Mr. Lake, already harassed by complaints by patrons, was consoled by co-organizer, Aimee Webster, with characteristic caustic humour: “Just tell them that the shock absorbers are not working alright, but unfortunately the new noise nullifiers have not yet arrived!” In short and in point of fact, what we need is a new theatre – far from the madding crowd – or there soon won’t be any kind of a crowd inside the theatre.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 1957

Impressions of Jamaica – then and now

By May V. Lopez

[. . .] Maybe I fell asleep, but at any rate, I dreamed of the Jamaica of my youth, those gentle, uncomplicated days. [. . .] Through my dreams, I seemed to hear the old street cries. “The lemon sugar candy goin’ pass, the peppermint sugar candy goin’ pass,” and the musical cry of the Pindah Bwoy.

I was just about to call, “Come here with the peanuts!” when I awoke with a start for a voice was intoning, “Please fasten your seatbelts, we shall be landing at the International airport of Kingston, Jamaica in seven minutes.”

SUNDAY, JULY 22, 1962

‘Roots and Rhythms’ – dance show for Independence

A time to rejoice – Out of Many One People. The spirit and motto of the new Jamaica will be gathered up in the dance show, Roots and Rhythms, which is being devised by Rex Nettleford and Eddie Thomas as part of the Arts Celebration Programme to make Independence. [. . .]

For the occasion of Jamaica’s Independence Celebrations the following ten major items are being presented. [. . .]

4. JAMAICIANA by Ivy Baxter. A number of dances done to Jamaican folk tunes and in a style developed by pioneer Ivy Baxter, showing the free and lyrical movement pattern of people in the Jamaican countryside. In this number, assisted by the Canboulay singers, folk songs are actually sung and street cries brought in to create atmosphere.

MONDAY, JANUARY 9, 1967

Value of peanut

By Theophrastus

[. . .] No longer do we hear in Kingston the old-time melodious sing-song street cry of the peanut vendor, as he plies his push-cart with roaster: “Pindar, roas’ pindar gwine by. If you want fe know me name, if you fe know me name, if you want fe know me name, jess axe de pinday bwoy, roas’ pindar!”

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 1967

Research officers appointed for history, creative, performing arts project

[. . .] Miss Jeanette Grant has been appointed Research Officer to collect folk tales, folk traditions and folk history. Miss Grant holds a Masters in English from Howard University. She has already started field work and is concentrating at present on collections in St. Thomas, Clarendon, and St. Catherine. This project aims at compiling material on folk history, riddles, ring games, folk proverbs, local legends, place names and names of people with a story, folk accounts of events, tales on dreams and their interpretations, street cries, and verses. Miss Grant is based at the Institute of Jamaica.

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 4, 1969

Paper on cultural heritage programme tabled

A paper on the cultural heritage programme of the Jamaica Government was tabled in the House of Representatives yesterday by the Minister of Finance and Planning, the Hon. Edward Seaga.

The paper stated: “I have to inform this Honourable House of the plans which are now in progress for the Cultural Heritage Programme for the country.” [. . .]

“There has been, in the past, a strong tendency to overlook the folk culture of the country. Several projects have been initiated by me to try and collect and preserve the wealth of folk material which is in danger of dying out for want of proper documentation.”

The Folklore Research Project: this project began officially in October 1967. The purpose of the project is to make, in as complete a form as possible, a collection of Jamaican folklore, categorizing and analyzing the information collected, so that the historical as well as the sociological significance behind the stories, customs, beliefs, etc. might be made available to students of folk culture in a scientific and systematic fashion.

The Research Officer employed on this project has travelled extensively the length and breadth of the island, collecting proverbs, riddles, legends, sayings, verses, street cries, dreams, psychic experiences, beliefs and customs. She has also collected a wealth of material from different cults and groups all over the island and has attended ceremonial rituals, revivalist meetings, etc.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1971

Capacity crowd for singers

A turn away crowd was on hand to greet the Caribbean House Festival Chorus in their 2nd annual concert at the 2,200 seat Brooklyn Academy of Music. [. . .] A steady flow of songs, dances, and medleys kept the audience swaying, clapping and laughing. Street cries from Trinidad and Jamaica; work songs from Martinique and Haiti; plaintive songs from Barbados and the Bahamas; joyous songs from Guyana and elsewhere in the islands made for a varied and expertly conceived show.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 1990

The vendors and their street cries

Willard House was established in the late 1890s, at 85 King Street, specifically to fill ‘the need of hotel accommodation free from the objectionable nature of an alcoholic bar.’

The patrons of Willard House were, therefore, not amused by the early morning street cries of the bottle collector . . . ‘An-y wi’ pi, an-y chapai, an-y whis-key bot-l,’ which meant ‘Any wine pint, any champagne pint, any whiskey bottle.’

More to their liking was the cry of the pear seller, always a woman, whose musical cry ‘ripe pear fe breakfus, ripe pear’ used to charm passionate lovers of this food of the Gods.

As with pear-selling, starch selling wass wholly and solely a female avocation. A King Street celebrity of the 1890s was Olivia, who did a good trade every morning as she marched down King Street to Victoria Market with a bowl on her head crying, ‘Starch! Starch! Washerwoman starch!’

The trade calls grew throughout the day as the vendors made their often weary walks of six to twelve hours, through a broiling sun and dusty streets. The only not troubled by the sun were the ice cream vendors. They came out only at nights with little glass models of houses, brilliantly illuminated, balanced on their heads, yelling out what sounded like “I scream” at the top of their voices.

In contrast was the peanut vendor with his matter-of-fact, rollicking, “Pea-nuts, pea-nuts, nuts, pea-nuts, pen-ny nuts.” The shrill pipe-like whistle, caused by the steam escaping from a gunnel on his diminutive top-covered hand-cart, heralded his coming. The nuts were served hot and direct from the pan, which was kept on a coal fire in the cart. The continuous shrill piping was a sound much loved by children, just as the cry of the chimney sweep swept fear into their hearts.

Ringing his bell, the chimney sweep was a fearsome, sooty creature, with ragged clothing and long-handled brooms and husky voice which kept repeating “keep you chimbley clean! Tek cyah fire bun.” He was the bogey man of every child.

The chants used by the great army of fruit and vegetable sellers were heard through the day.

“Yellow-heart breaffruit gwine pass

Lucy yam gwine pass, eh, de dry

Lucy yam gwine pass

Sweet orange gwine pass

Green banana gwine pass.”

The cries were accompanied by the slip-slop of the san-pattas (a kind of sandal) on the women’s feet. This changed in the 1920s when the then governor, Sir Leslie Probyn, successfully instilled into the heads of the people that they should wear boots, if possible at home, but always in public.

Christmas time brought out the card sellers. With their glitter and satin-padded cards they would stand outside the General Post Office on King Street crying “Seal ‘n’ stamp! Lady, seal ‘n’ stamp!”

In more recent times, during the months of March to July from about seven to eleven o’clock in the morning, girls would walk up and down King Street and its environs with trays filled with spotted booby eggs. Shoppers would stop them to exchange their pennies for the hard boiled eggs seasoned with black pepper and salt.

The eggs, which are rarely seen today, were collected from the sooty tern and brown noddy by fishermen on the cays outside Kingston Harbour.