The Sirens of Hampton

LONDON HAS few interesting and purposeful sounds which are broadcast regularly across a wide area. The era of steam engine whistles, dockyard sirens and factory hooters is long gone and the city doesn’t have an equivalent of Edinburgh’s one o’clock gun. Church bells and clock chimes are pretty much all that’s left.

An exception, itself a survivor from an earlier age, is the warning siren at the Hampton Water Treatment Centre by the Thames, a mile or so to the west of Hampton Court. I learned from discussions on local forums and blogs that the siren was of the old-school kind whose note rises and falls, just like the ones in footage from the Blitz and Cold War-era Protect and Survive public information films. Double bubble!

The sound is instantly recognisable from countless films and documentaries and, to my ears at least, it is an obscurely moving one. The sirens were manufactured in large numbers by a variety of firms in Britain during the Second World War and they were retained until the 1990s as part of a national network in the event of nuclear attack. Those that are left today are found at nuclear power stations, chemical plants, oil refineries, and to warn of flooding.

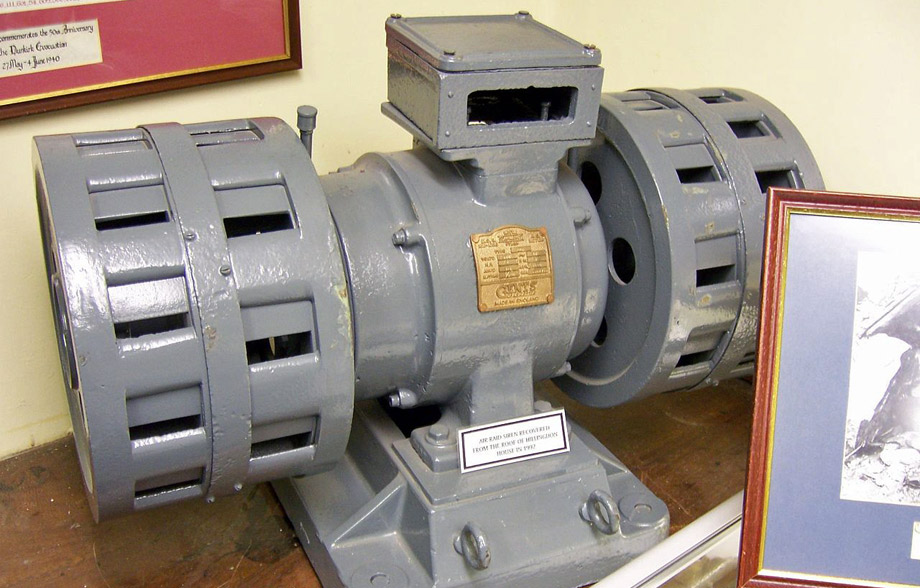

The Creative Commons-licensed photograph below by Harrison49 on Wikimedia shows the siren, made by Gents of Leicestershire, which had served at RAF Uxbridge until its removal in 1992. This, or one very much like it, is the kind which is at Hampton.

The Water Treatment Centre stores chlorine and other hazardous substances on site for sterilising the drinking supply. This requires plans for the evacuation of the surrounding area in case a storage tank ruptures or there’s some other kind of leakage, hence the regular siren test. Thames Water’s press office kindly confirmed that the test is done every Tuesday at 9am but, no, I couldn’t go inside the Centre to get a photo of the siren because it’s a high-security area.

I guessed the siren would most likely be somewhere in the cluster of workshops and administrative buildings at the eastern end of the complex, so I set up the mic and recorder in Hurst Park on the opposite bank of the Thames, away from busy roads. A rough rule of thumb is that as you go towards the outskirts of London, people become friendlier and more approachable. This was so with the dog-walkers in Hurst Park and the sight of the mic in its big fluffy windshield was a good ice-breaker. Out of the eight or nine people I spoke with, only one wasn’t aware of the siren at all. Everyone else knew of it and the time it went off. Some guessed it was to do with flood warnings.

The bell of St Mary’s Parish Church struck the hour and the siren began a few seconds later, rising quickly from a low growl to its full, tuneful volume. The test is necessarily brief, but during that moment I felt how thrilling it would be if there were siren tests everywhere, at least once a week, and for a good minute or more at a time. On the hearing the sirens, everyone would be required to do something: perhaps stand on one leg, or shake hands with the nearest person.

There is only a long way round from Hurst Park to the waterworks itself via Hampton Court Bridge. I packed up and set off to have a closer look. The waterworks began at Hampton in the middle of the 19th century so that water could be drawn upstream of the polluted, tidal stretch of the Thames. Three London water companies established themselves there before they were amalgamated into a single municipal organisation. The original buildings still stand, presenting grand symmetrical profiles to the Thames faintly reminiscent of the Old Royal Naval College at Greenwich. Smaller buildings from different eras are dotted among them.

The whole complex is the size of small town, much of it behind high fences with quiet ponds and reservoirs visible, conical mounds of sand and gravel perhaps thirty feet high, pipes with shut-off valves sized for giants’ hands. It is slightly surprising that this watery metropolis doesn’t seem to have a museum of its own, although the narrow gauge railway which once served it is now preserved and operated by enthusiasts.