Blog

Occasional posts on subjects including field recording, London history and literature, other websites worth looking at, articles in the press, and news of sound-related events.

London runs on war and rumour: Chaucer in the House of Fame

ALL-SEEING IS usually taken to mean the same thing as all-knowing and, until quite recently, it was thought to be the prerogative of the Biblical God. But people can be ambitious. In the late 1780s Jeremy Bentham proposed a new design of prison called a Panopticon, the design of which would allow the governor and staff to see everything the inmates did. It would be, wrote Bentham, a ‘new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example’.

More obscure are early anticipations of systems in which everything can be heard. A blog post I wrote a while back alluded to Charles Babbage’s theory of the persistence of sound and its influence on Charles Dickens. The theory is foremost a moral one: the sound of everything we say and do becomes attenuated but never entirely disappears from the atmosphere, and so will be there on the Day of Judgement as evidence of our conduct. It’s explained in Chapter IX of Babbage’s Ninth Bridgewater Treatise.

Before that, another Panauditon had been dreamt up by William Baldwin in his 1552 novel, Beware the Cat. The narrator drinks a magic potion which allows him to hear everything happening within a hundred-mile radius of London. This overwhelming experience ends badly.

Geoffrey Chaucer’s The House of Fame was written while he was still living in London at the end of the 1370s. It’s an allegorical poem in which the narrator falls asleep and dreams that a giant eagle carries him to the realm inhabited by Fame, personified as a goddess. It’s where all the utterances ever spoken float up to and linger, particularly those concerning people’s reputations. In Middle English, ‘fame’ denoted reputation in general, whether it was good or bad, and was etymologically related to acts of speech similar to what we understand as ‘hearsay’ [1].

This would have been a topical subject for Chaucer’s audience. The act of scandalum magnatum, meaning the defamation of the King and his ‘magnates’ so as to produce discord, had been established by the First Statute of Westminster in 1275. Against a backdrop of political intrigue and popular discontent, the definition of ‘magnates’ was clarified in 1378 to include peers, prelates, justices and various named officials [2]. This post is concerned with the different ways sound features in The Hall of Fame, and particularly how they might have been influenced by Chaucer’s life and experiences in medieval London.

The poem is over 2,000 lines long and you can find a version in Modern English as a PDF via the eChaucer site. A slightly livelier rendering can be found on Richard Scott-Robinson’s eleusinianm site. Three sound-relevant sections of the poem are examined here in the sequence they occur. In the first, the giant eagle tells the poet about the nature of sound and why it travels upwards. In the second, the poet encounters Fame and hears great multitudes petitioning her about their reputations. In the final section, Chaucer describes a vast wickerwork structure in which everything that’s ever said is gathered together and can be heard.

TRAVELLING BY EAGLE

The dream begins with the poet finding himself in a glass temple containing brass tablets on which is engraved the Aeneid. A huge eagle then appears to snatch the poet up in his claws before flying off. Whilst in flight the eagle lectures him on the nature of sound and how it inevitably rises to the House of Fame:

The eagle’s chummy familiarity (at one point he addresses the poet as ‘Geoffrey’) suggests he may represent someone known to Chaucer and his well-to-do circle, underlining the theme of reputation. An educated audience would also likely have recognised the allusion to the Roman philosopher Boethius’s theory of sound waves. The part about sound rising might also be drawn directly from Chaucer’s own experience of living in the city.

Chaucer was born in London around 1343 and spent his childhood at the family home between Thames Street and the Walbrook stream, near where Cannon Street station is today. 14th-century records describe it as a ‘tenement’ but this was meant in the old sense of a property holding. Chaucer came from a wealthy background and the home was a substantial one, likely consisting of cellars, a large main room or hall plus kitchen at ground level and upper rooms called ‘solars’ [3]. These may been reached by stairs and a wooden gallery encircling the main hall [4], and we can imagine the gallery providing a good vantage point for the young Chaucer to eavesdrop on adult conversation rising from the hall.

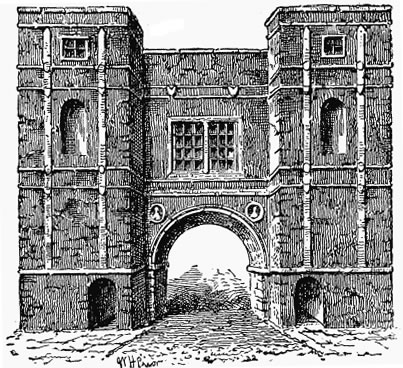

What is known for certain is that, between 1374 and 1386, Chaucer lived above street level while working as a customs official, responsible for the important commodity of wool. In anticipation of starting the job he took out a lease from the city authorities for an apartment above the Aldgate and was living there when he wrote The House of Fame.

Despite London losing around half of its population during the Black Death of 1348–50, the city would have been a thriving mercantile and administrative centre during the time of The House of Fame. The poll tax of 1377 counted just over 23,000 lay tax-payers in London [5], suggesting a total population of as many as 40,000 with a density equivalent to modern-day inner London boroughs like Hackney and Kensington & Chelsea. The sounds of the streets and the ceaseless daytime traffic through the Aldgate would certainly have risen to Chaucer’s lodgings, pressing on him most during time spent alone. The eagle may be alluding to Chaucer’s solitary home life when he again assumes familiarity with the poet:

IN THE PRESENCE OF FAME

After the eagle has set him down safely, the poet climbs a hill at the top of which he finds ‘a building that was so beautiful that no living man could possibly have the ability to describe it adequately’, although Chaucer has a good try. It is made of beryl and gold, and filled with musicians and shouting multitudes:

Crowds of people ‘from every region of the Earth’ swarm forward to petition the goddess Fame, who is equipped to see and hear everything around her:

The requests range from everlasting renown to complete obscurity, and Fame variously grants, refuses or delivers their complete opposite in an unpredictable way. Her decisions are broadcast around the world by Aeolus, the god of the winds. A ‘rabble’ ask that, although they’ve all led lives of indolence, they be remembered as being loved madly by women. But they’re out of luck:

Chaucer places one significant limit on how arbitrary Fame can be in her rewards and has her refuse the request of a group of traitors to be remembered well. Otherwise the sounds of crowds and music, heralds’ proclamations and petitions from groups are magnifications from events in city life with which Chaucer would have been familiar. An account from 1417 of Henry V’s victory parade through London shows how extravagant these could sometimes be.

LONDON IN WICKER

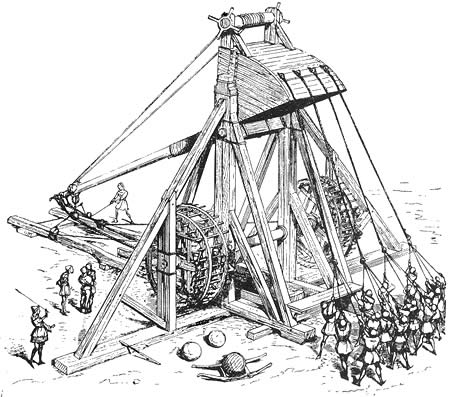

The poet is left with unanswered questions. During their flight together, the eagle had promised he would be shown how utterances, once in the House of Fame, become physically embodied in the forms of those who spoke them. On explaining that he hasn’t yet seen this, a helpful stranger leads the poet to a valley where a vast wicker structure, sixty miles long, revolves ‘as swiftly as thought’ with a great roaring noise like a stone being hurled by a siege engine. This sound detail is significant because it links the workings of the House of Fame with warfare.

Chaucer would have had first-hand experience of artillery pieces like trebuchets at the siege of Reims in 1360, where he was captured and ransomed by the French, and during later military expeditions under the leadership of John of Gaunt.

Trebuchets were among the most impressive machines of their time and it is hard to imagine what else might have sounded like them. Chaucer’s job of supervising the collection of wool duties in London would have given him an acute understanding of the importance of such revenues in funding armies and their siege engines, and how in turn warfare contested England’s access to the wool markets of continental Europe.

From his vantage point, the poet sees how wicker house is ‘full of things hurrying’, suggestive of rodents swarming around the Thames wharves and warehouses, and from it new sounds can be made out, not only ‘loud creakings’ but also voices:

The eagle returns and lifts the poet inside the wickerwork so he can finally know what happens within the House of Fame.

All the truths and lies ever uttered exist in a state of competition within the House of Fame, before combining in synthesis and escaping to the wider world. It is a house in the sense that it is a single, unified structure, but in all other respects a metropolis: London as a combined rumour mill, information centre and war machine.

In recent years there’s been debate among scholars as to how London influences Chaucer’s works against earlier claims of its absence [6]. I hope I’ve shown how Chaucer’s own experiences of living in London, both in his lodgings above the Aldgate and at large, inform The House of Fame. But it also illustrates the primacy of the spoken word, of gossip, dispute and rumour as representing the essence of city life in medieval thought. This was a world in which the social metaphors of eavesdropping and being close to or distant from others were much more strongly grounded than today in the physical realities of proximity and being within earshot.

In attempts to study and even simulate the sounds of the past a distinction can be made between what I call the easy and the hard problem of sound history. The easy problem involves the realm of artifacts and animals: the acoustics of buildings, musical instruments and machinery, the layout of the streets, the presence and numbers of livestock. Many such issues can be abstracted away from their social context. But the hard problem is always a social one because it asks who was saying what to whom.

1. Flannery, M. (2012). John Lydgate and the Poetics of Fame, Boydell & Brewer.

2. Plucknett, T. (1956). A Concise History of the Common Law, Little, Brown and Co.

3. Benson, L., Pratt, R., & Robinson, F. (1986). The Riverside Chaucer, Houghton Mifflin.

4. Brewer, D. (1978). Chaucer and His World, Eyre Methuen.

5. Saul, N. (2008). Fourteenth Century England: Volume 5, Boydell Press.

6. Butterfield, A. (ed) (2006). Chaucer and the City, DS Brewer.

ABOUT SOUND

FIELD RECORDINGS

The balloonist in the desert is dreaming

The Binaural Diaries of Ollie Hall

GEOGRAPHY AND WANDERINGS

The Ragged Society of Antiquarian Ramblers

LONDON

ORGANISATIONS

Midwest Society for Acoustic Ecology

World Forum for Acoustic Ecology