Introduction • Chelsea Harbour • Mouth of the Westbourne • Custom House Stairs • Jane Parker, Wapping • Nicola White, Greenwich • The Albert Basin • Rainham, Essex • Aveley Marshes, Essex • Procter & Gamble, Thurrock • Peter Beckenham, Swanscombe • Tilbury Docks • Shornemead Fort, Kent • Coryton Refinery, Essex • Allhallows Marshes, Kent • Maplin Sands, Essex

DOWN OLD BILLINGSGATE to the Thames, past the toffee peanut stall minded by a roster of men who appear two or three at a time, and then eastwards along the Thames Path to the Custom House Stairs. The way is busy with tourists and some stop to look down the stairs at the foreshore's clutter or the tawny-coloured river, depending on the tide, before moving on.

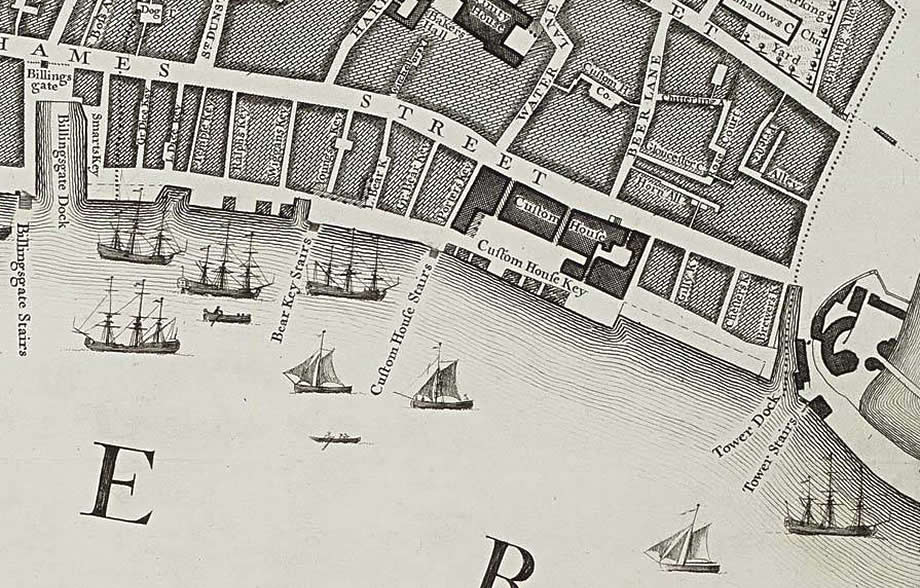

The Custom House itself is immediately to the north-east and different buildings with the same function have stood on that site since at least the late 14th century, when Geoffrey Chaucer oversaw the collection of wool duties. The stairs are listed in Lockie's The Topography of London from 1810 and they also appear in Roque's map from 1746:

The solemn granite steps and blue-painted railings at the top suggest the Custom House Stairs are meant to allow someone to get on and off the foreshore, but maybe not you. The older and wealthier parts of London are full of such quiet nudges to encourage you to stick to your proper place. Nonetheless, anyone can use them if they want to since they are watermen's stairs and were once the equivalent of bus stops or taxi ranks.

Seven sets of watermen's stairs are left on the City of London side of the Thames. From west to east they are: Trig Lane, Upper and Lower Vintry House, Cousin Lane, Upper and Lower London Bridge, and Custom House. The Vintry House Stairs no longer give access to the river.

Steps of some kind leading down to the river have likely existed since very early times, but their numbers grew from the Tudor period as the Thames shore began to be walled in. This coincided with a rise in the status of watermen who, in 1510, were granted an exclusive licence to carry passengers on the river. The stairs became recognised places from which the watermen conducted their trade. Competition among them for passengers could be lively, as recounted by Ned Ward in The London Spy, written between 1698 and 1700:

We turn'd towards Billingsgate, where a parcel of fellows came running upon us in a great fury, crying out as I thought, 'Scholars, Scholars, will you have any whores?' Notwithstanding I told 'em we wanted no whores, nor would we have any, yet they would scarce be satisfied. My friend laugh'd heartily at my innocent mistake and undeceiv'd my ignorance, telling me they were watermen who distinguish'd themselves by the titles of Oars and Scullers, which made me blush at my error, like a bashful lady that had drop't her garter.

Ward's joke partly relies on the watermen dropping their aitches so that oars becomes mistaken for whores, suggesting this class distinction in London speech has been around a long time, outlasting other habits such as substituting vs for ws.

Many of the stairs themselves haven't endured either and public access to them has long been contested. According to Joan Tucker's book Ferries of the Lower Thames, a City ordinance of 1417 stated:

Certain persons who hold wharves and stairs have been making profit by charging one penny or tuppence or more for them to wash their clothes, taken their water which they have done time out of mind, whereas those persons pay nothing for the land they occupy. The common good has been supplanted. It is ordained that they shall not disturb or molest any one fetching, drawing and taking water or beating and washing their clothes. On pain of imprisonment.

Several sets of stairs were demolished during the 1860s as Joseph Bazalgette directed the construction of the Thames Embankment. Another convulsion of development beginning in the 1980s saw the loss of more stairs around the Pool of London and further downstream. But some still survive. The Wapping Old Stairs are next to the Town of Ramsgate pub and they were once well-known enough as a landmark to be celebrated in a popular broadsheet ballad:

Your Molly has never been false, she declares,

Since the last time we parted at Wapping Old Stairs;

When I said that I would continue the same,

And gave you the 'bacco box marked with my name.

They were also depicted in watercolour and ink by Thomas Rowlandson. The picture is undated, but Rowlandson was born in 1756 and died in 1827, so we might assume this is how the Wapping Old Stairs looked around the beginning of the 19th century.

Many of the stairs can be slippery with river muck and have to be negotiated carefully. Railings and grab chains don't always dispel the thought that you too might end up in the ranks of the drowned, like those recorded since medieval times in the Letter-Books of the City of London. The fragility of human life is somehow made more clear by the simple, unadorned language of the reports: the man who fell asleep on London Bridge and so toppled over the edge, another whose small boat went from under him as he leaned forward to place a barrel on the quayside. Also, the nine-year-old child who, on the 21st of September 1275, slipped near where the Walbrook once joined the Thames:

Friday after the Feast of St. Matthew information given to the aforesaid Chamberlain and Sheriffs that Katherine, daughter of Thomas de Brackele, of the age of nine years, was found drowned under the wharf of Peter Cusyn in the parish of All Hallows at the Hay, in the Ward of Douegate. Inquest thereon. The jurors (drawn from the said Ward and the nearest Ward of Henry de Coventre) find that late on the preceding Tuesday the said Katherine went to a certain common bridge situate near the aforesaid wharf, and descended the steps of the said bridge for the purpose of washing her feet, and whilst stooping down to raise water with her hand she by accident fell into the water and so was drowned.

The tide rises at the Custom House Stairs and the wash from passing boats arrives. Small waves combine to send a single hump of water bounding up the steps, as if the river is glad to meet you at last.

Introduction • Chelsea Harbour • Mouth of the Westbourne • Custom House Stairs • Jane Parker, Wapping • Nicola White, Greenwich • The Albert Basin • Rainham, Essex • Aveley Marshes, Essex • Procter & Gamble, Thurrock • Peter Beckenham, Swanscombe • Tilbury Docks • Shornemead Fort, Kent • Coryton Refinery, Essex • Allhallows Marshes, Kent • Maplin Sands, Essex